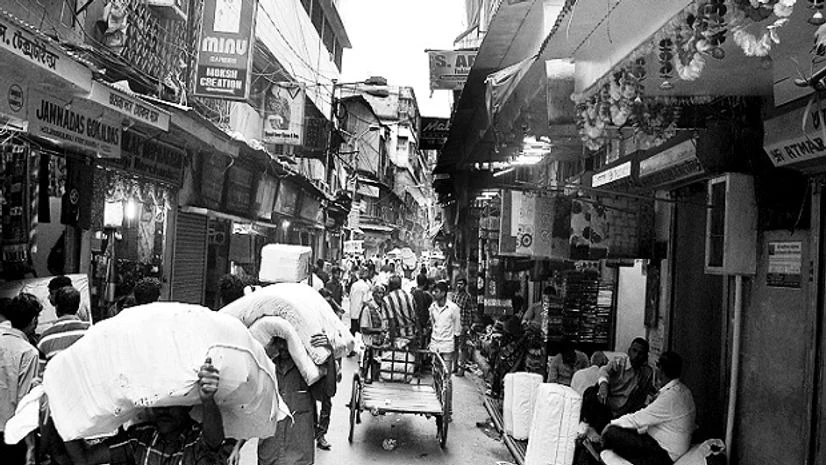

December is usually a busy month for traders in Kolkata’s Burrabazar market, which is counted among Asia’s largest wholesale markets. While small-time traders throng the market to buy articles such as plastic toys, iron utensils, clothes and artificial jewellery to sell in village fairs, the wedding season keeps the traders of spices, dry fruits and commodities busy.

This December, Burrabazar, which has weathered many global economic slowdowns, is seeing much thinner crowds. According to traders, demonetisation has eroded roughly half of Burrabazar’s total trade.

Balaram Saha, an iron utensil merchant in the Rajakatra area of Burrabazar, has been following the same norms of business as laid down by his forefather during the British era.

“Our entire business runs on credit and cash. People buy utensils in the morning, sell them by the evening, pay the next day, and buy new supplies,” said Saha. After demonetisation, his sales have come down from Rs 1,000 to Rs 500 a day.

Burrabazar is a highly unorganised market with hardly any estimates of its size in terms of turnover. The area is divided into several smaller markets with Posta Bazar, which is the wholesale mart for foodgrains, spices and commodities such as potato, garlic and onion being the biggest sub-market. There are close to 25 such small markets or katras in Burrabazar. Most of the traders in the area are middlemen who interact between suppliers and retailers.

According to Biswanath Agarwal, honorary secretary, the daily turnover of the market would be close to Rs 200 crore. “Now, only 25-30 per cent business is left. Since everything is settled in cash, we are waiting for cash availability to regain normality in business,” said Agarwal.

More From This Section

“Our business has come to a halt. It has gone down by more than 90 per cent in the past few days,” says Samata Talikdar, a dealer of ropes in Rajakatra.

Spices in Burrabazar are sourced from Unjha in Gujarat. The entire business is paperless, or without receipts, and runs on credit. “Getting a receipt is a big problem as suppliers don’t want to provide it. Sometimes, if we buy things worth Rs 100, we get bills worth Rs 60,” said a spice trader at Rajakatra on condition of anonymity.

Adjacent to Rajakatra is Jamnalal Bajaj Street, the wholesale market for clothes and yarns, one of the earliest trades of Burrabazar.

Soon after demonetisation, Anand Harlalka, who runs a cloth shop in the area, bought a swipe machine. However, his swipe machine has hardly been used since it was purchased.

“We haven’t got any major response after installing the swipe machine,” says Harlalka.

Kamal Binani, who used to sell saris worth Rs 10,000-12,000 every day prior to demonetisation, has seen daily sales come down to Rs 1,000-2,000. He now plans to buy a swipe machine, but feels it is unlikely to improve sales.

“This market has no place for cashless transactions. We work on credit. Our customers are from rural areas and they only deal in cash. However, in the long run, we might have to buy a swipe machine,” Binani said.

Burrabazar is also a wholesale mart for plastic articles, especially toys.

Mohammand Heera, who sells tarpaulin, has seen daily sales come down from Rs 2,500 to less than Rs 1,000 a day. In addition, the suppliers have increased the prices by Rs 2 per kg on account of higher transportation cost, further reducing Heera’s margin. “We don’t have money to buy new supplies. There is no demand. At the same time, prices have increased. Unless cash becomes available again, we see no signs of improvement in sales.”

Till the time liquidity comes back into the system, Burrabazar, also known as Mini India, is unlikely to return to normalcy. Ironically, while the government aims to move towards a cashless society, Burrabazar eagerly awaits the return of cash to beat the biggest slowdown it ever faced.

)