At 37,000 Mw, renewable energy accounts for close to 15 per cent of the total power capacity in the country. It sounds impressive till it is compared to the humongous target India has committed for the Paris climate change agreement - 40 per cent of the installed capacity by 2030.

Experts within the government calculate that 300,000 to 350,000 Mw of renewable energy would have to be set up to meet this target. To put it in perspective, India is aiming to add 175,000 Mw of capacity from clean energy sources by 2022: 60 per cent from solar energy, 30 per cent from wind and the balance from biomass and small hydro.

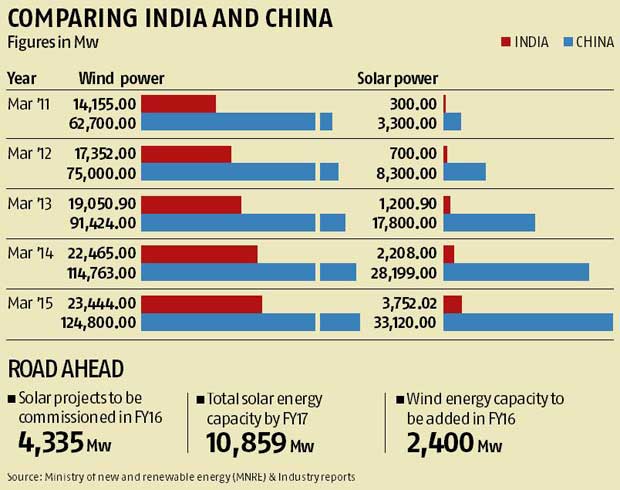

Considering where India started from in 2010 (when the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission became active), the growth of solar power in India has been phenomenal - from 2 Mw in 2010 to 4,200 Mw at present. In wind energy, India is the world's fifth largest producer at 24,000 Mw.

The fairy tale ends here.

Losing appeal

In wind power, growth has decelerated in the past three years. Seen as a tax haven, the investment in wind dropped once the government pulled the plug on the accelerated depreciation tax benefit for the sector in 2011. It was later brought back and then another 'generation-based incentive' was also introduced.

This, however, has not excited the power producers so far. From annual addition of 3,000 Mw till 2011, it has dropped to 1,500-2,000 Mw every year. In the current fiscal, against a target of 2,400 Mw, only 644 Mw has come up so far.

Solar power may have got greater policy impetus after the National Democratic Alliance came to power but ratcheting up capacity at rates no country has done before is a tough task when seen from where India sits at present.

Currently, on an average, the country is adding 1,000 Mw of solar power annually. At this rate, 100,000 Mw in six years looks farfetched even if one was to assume that India can match China which has added solar capacity at an ever increasing rate. The Union ministry of new & renewable energy pegs the annual growth of solar power at 15,000 Mw. Privately, senior officers say the country would touch 6,000 Mw by the end of this fiscal and close to 10,000 Mw by next.

Upendra Tripathy, secretary, ministry of new & renewable energy, is a confident man though. "We are on track to achieve 175,000 Mw. We are inviting investment in both generation and grid capacity addition. I can't comment on the climate change targets but as for renewable energy, we will achieve the targets we have set for the country."

"The target trajectory for renewables is stunning and could lead to a complete transformation of the energy sector in the country. Clearly, in the near term, we need to focus on the financials of the distribution companies, transmission constraints, the ability to pass on the true cost, and consumer affordability," says Rupesh Agarwal, advisory partner and leader (energy), BDO India LLP.

Infrastructure hurdles

The target would have looked more plausible if only the evacuation infrastructure was in place. The southern region which is surplus in wind power has a transmission deficit. So is the case with Rajasthan, Jammu & Kashmir, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh and others. The ambitious 'Green Energy Corridors' project envisaged in 2011 as an alternative transmission network has been a non-starter with no major lines being built or tendered out. It's only now that the government has decided to 'nominate' state-owned Power Grid Corporation to build it with assistance from the states.

Power Grid, which designed the plan five years ago, calculated the total expenditure at Rs 40,000 crore. The cost is five-fold now with targets being revised in the same quantum.

Tripathy says his ministry is trying to avoid any mismatch between generation and transmission capacities. "We have said that the investment in generation and grid should be 1:1. Currently it is 1:0.4. We want that by the time this renewable energy capacity comes up, there is enough grid capacity."

Amid all this, the point being ignored is that renewable energy is an intermittent power source and grid-connected renewable energy would need the same amount of conventional energy as balancing power. Thus, there is equivalent coal- or gas-based capacity that needs to be built or fired along with renewable energy.

NTPC, for instance, can bundle thermal power and renewable energy and sell at an average rate. The bundling and the sale would also face tariff challenges. Solar power is priced at Rs 6-8 a unit and wind power at Rs 4 a unit. Bundled power would be Rs 3.5-4 a unit.

There are no buyers for expensive power. The financially stressed state utilities are not willing to buy even conventional power even at Rs 3 a unit. The historic drop of price for solar power to around Rs 5 is actually scaring away investors. Solar energy at that price is not viable in the country currently. Moreover, there is the absence of financing options.

"The biggest financial challenge faced by developers has been access to low-cost finance. While developers using imported components and cheaper EXIM Bank loans (10 per cent interest for 18 years) have thrived, those using indigenously manufactured equipment have had to avail costlier loans (13 per cent for 10 years). This has diminished the confidence among the investor community," says Amit Kumar, partner (energy & utilities), PwC India.

As another officer involved in setting the climate targets puts it, "If we can do the 175,000 Mw target by 2022, reaching the 2030 target is not going to be tough. But the 2022 target was not really a bottom's up assessment - it was an ambitious round number."

Experts and investment trackers are still maintaining their stand that there are big investors betting on India's renewable energy sector but are sitting on the fence awaiting clarity on policy.

)