The fields by the side of the Kana river in Dhaniakhali, an administrative block in Hooghly, are generally lush green this time of the year. But this year brown has replaced green, a sight uncommon in West Bengal.

In nearly 65 years, Kashi Patra, a farmer leader in Dhaniakhali, has not seen as dry a spell as now. The Kana river, the principal source for irrigation, has turned into a dry soil bed and the numerous ponds have transformed into depressions of cracked soil. “It’s a near-drought situation,” says Patra.

Read more from our special coverage on "DROUGHT"

Water reservoirs at the Damodar Valley Corporation are a major source of irrigation in Dhaniakhali from December onwards. After the monsoon, water replenished in the reservoirs is used for irrigating potato, paddy, jute and vegetables between January and May. However, last year, there has been almost no rainfall between August and December.

During the boro paddy season (January-April), around 2,000 of 6,000 hectares could not be irrigated in Dhaniakhali, according to an official in the agriculture department. With little river and dam irrigation, farmers are relying on deep tube wells. But a prolonged dry spell has made that unsustainable, too. Groundwater has dipped so much that even tube well irrigation is not possible, according to Nepal Chandra Das, a panchayat official at Dhaniakhali.

With cultivation taking a hit, farm incomes have come down for both farmers and farmhands.

Harichandra Das owns about 2.5 acres in Dhaniakhali. His income from potato farming has been just enough to plough back the cost of production. In the absence of water, a large part of his crop was infested with pests.

Jute farmers are bracing up for losses. Against a cost of production of Rs 7,000 a quintal, the market price of jute is Rs 5,000-6,000 a quintal. “Almost half of our jute crop was destroyed by the heatwave and lack of water,” says Das.

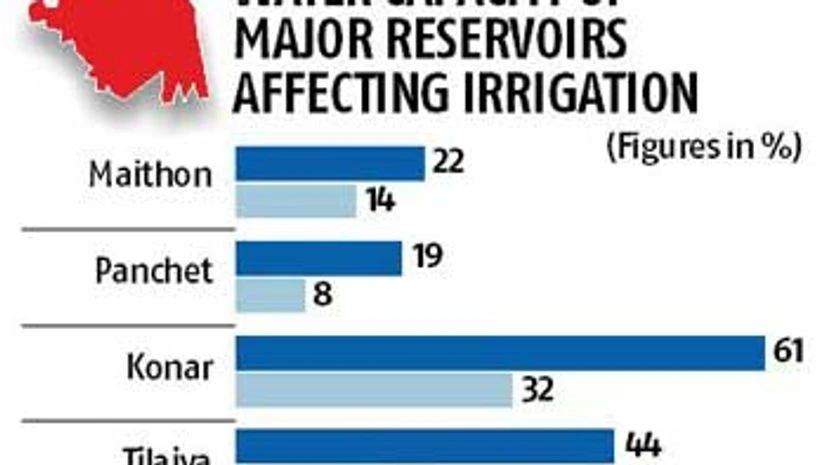

The level in almost all the major reservoirs from which West Bengal draws water — Maithon, Panchet, Konar and Tilaiya — is lower than last year. According to the Central Water Commission, water in reservoirs in the eastern region is 30 per cent of capacity, against 42 per cent at the same time last year.

“Irrigation from reservoirs in the boro paddy season is for 1.2 million hectares. This year, it has been not been more than 1.05 million hectares,” says an engineer in the West Bengal irrigation department.

Farmers are worried about loan repayments. “Last year, the government had restructured loans. We have submitted a plea with the government for a similar facility this year,” says Patra, the farmer leader in Dhaniakhali.

Banks have restructured a significant portion of crop loans in West Bengal for the kharif season. Farmers were given a year-long moratorium, extension of repayment up to five years and a facility to avail new loans for the rabi season. The drought in the early kharif season last year, followed by heavy rain, had led to a significant crop damage.

“Unless the government declares a drought, we cannot restructure loans. So far, there is absolutely no offtake for kharif loans as the weather conditions are not conducive,” says a United Bank of India executive.

)