A strange phenomenon has gripped India. We have stopped investing in public spaces. And the ones that do exist have been effectively privatised en-masse. Public spaces are technically any space that are open to the public. Those roads, squares, footpaths, parks, etc. that are meant for all to use are all public spaces. But, in India today, almost all public spaces have been taken over by individuals or groups of individuals, as is the case for the bulk of Delhi.

Modern India has been quite miserly with either the grandness or inclusiveness of its public spaces. To the knowledge of the author, the only significant public space created in recent times was by Narendra Modi's Sabarmati waterfront and Mayawati's parks. Gurgaon is a classic example where town planners did not even bother with footpaths, leave alone open parks and squares.

At this point, it would be easy to point out the grand public spaces created in cities the world over. But global examples will shame rather than motivate. Even the most despotic of Indian rulers created and maintained public spaces. The Mughals created public spaces, the Rajput kings created public spaces, the Afghan rulers created public spaces - and Sher Shah Suri was not the only one; the Cholas had their large temple complexes, the Marathas meticulously rebuilt the ghats of Benaras, and these are only a few examples. Public spaces have been an intrinsic part of Indian town planning from prehistoric times - think of Dholavira or Harappa. Even the British created public spaces, in the form of company baghs in the smaller towns and squares, not to mention wide footpaths and parks in their presidencies.

Think of any major city from India's past, or anywhere in the world today, and what comes to mind first is an iconic public space. These spaces are open to all, they have great aesthetic quotient, they are well maintained and act as a focal point for people to gather. And what have we in modern India? Pause. Think.

The absence of public space works directly against inclusive economics and progress. Public spaces enable economic, family and social interaction.

They enable a host of businesses, which otherwise would not survive. They provide a breathing space to men and women grappling with day-to-day pressures. Ideas evolve in public spaces, communities and social movements are formed in public spaces, disruption - the favourite current buzzword of technologists - is catalysed in public spaces. Our Independence movement was fought in public spaces.

Public spaces are what cities are about, and countries built on.

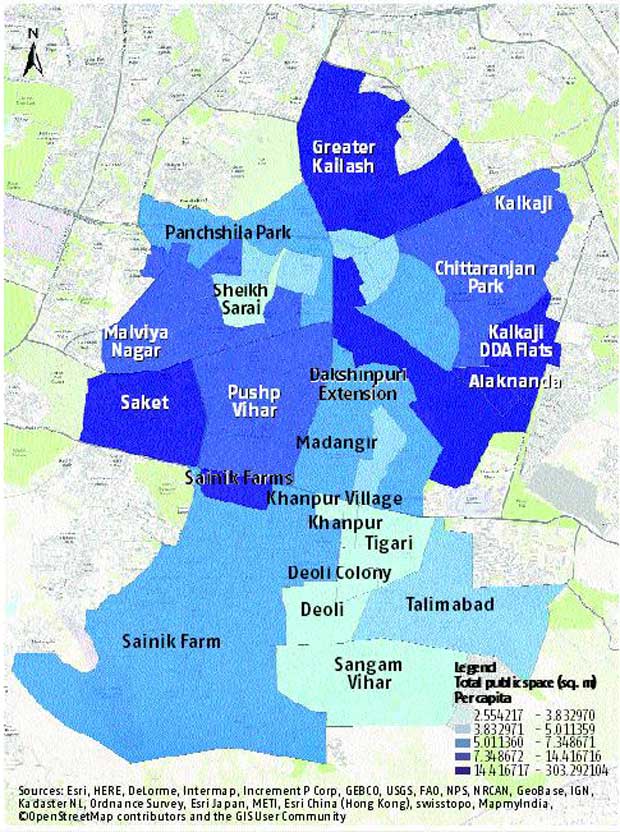

Using New Delhi's Greater Kailash and its surrounding areas as an example, we briefly decipher the story of public spaces in urban India. The poorest areas are informal settlements or slums as in Khirki and Sangam Vihar. These have almost no visible public spaces, apart from the narrow lanes that run through them. A temple or a mosque may have a small courtyard where adherents can safely gather, but that is about it.

Even those areas, demarcated for a park or playground, have been occupied and built upon. In the vicinity are government's schools with some open spaces, but these are also closed to the public. There also are no neighbourhood squares where families can gather. Though an urban forest land runs right through the middle of this area, it is only open for a few hours in the morning and evening, due to 'safety considerations'. There is simply no space where the people (especially the poor) can freely stroll, their children can play, their families can spend some time together, or friends can debate, or even where vendors can sell street food without the fear of eviction. As the accompanying map well illustrates, public spaces are no longer for the poor.

Next, consider the planned areas, which are typically more affluent. Modest public spaces were created, but they were taken over soon enough by individuals and groups. Footpaths are typically narrow, with trees right in the middle - a very Delhi phenomenon. The affluent have taken most of the remainder for parking; they get free space on a patch whose value runs into hundreds of thousands per square yard. And what is still left over, is occupied by vendors who provide services that percolate to the affluent. Everyone but pedestrians use footpaths in this constituency, as is the case in most other parts of urban India.Most middle and higher income societies or 'colonies' have put up barbed wire fences and gates due to 'security considerations' and outsiders are barred by private security guards. In markets as well shopowners have expanded their shops, taking over pavements. The parks in gated affluent neighbourhoods bar children and adolescents from playing, as it may hurt senior citizens or spoil the ornamental nature of the space.

This free-for-all is amazing in its magnitude and jugaad. Multiple governance structures have not only divided tasks between various government entities, they have also chopped up responsibility. And, in the absence of any disciplinary mechanism, whoever can, grabs whatever they can. In this free-for-all, the affluent can still make do, but the poor get the brunt of it. Poor women are naturally the most excluded from such public spaces, unless they work as maids for the affluent, in which case the spaces for the affluent become accessible.

There is only one class of places where public space is still relatively open - temples, mosques and mazars, gurdwaras and historical monuments. But they also place limits on who can enter and who cannot, at what time, etc. Gods and ghosts have their own extra-judicial powers that prevent private takeover of the space they occupy. But, surely building more religious spaces cannot be the only solution to India's space problem.

Public space ownership needs to be devolved to the community wherever it is contained within a well-defined area as that overseen by the Resident Welfare Association (RWA). Where the public space is outside the ambit of the RWA, a footpath on a main artery for instance, a single entity needs to be allocated its responsibility - whether it is the local government's municipal commissioner or the state government's public works department. Ownership and responsibility over public assets cannot be carved up.

PER CAPITA PUBLIC SPACES

The accompanying map is of Greater Kailash and areas to the south of it. The darker shaded areas have greater density of public space. The most affluent areas such as Greater Kailash, Saket, Chittaranjan Park, Alaknanda contain far more public space per capita than the slum areas of Sangam Vihar or Deoli. The only affluent area with relatively low public space is Sainik Farms, where illegal plotting has created large farmhouses with high private spaces per capita.

The author would like to thank Komal Nanda and Tisha Sehdev working on Nielsen India's Cellgrid Platform. The methodology processes satellite imagery from Isro and other entities to estimate built-up areas, green areas, open spaces, public spaces and population concentrations and incomes at the intra-neighbourhood or colony level.

)