JK Tyre and Industries Ltd says it is setting up a global research and development hub in Mysuru, where it has three factories, more than any other place in India. A little over 4,000 people are building tyres, for trucks to two-wheelers.

Yet, Umesh Krishna Shenoy, the vice-president (works), says he finds a daunting challenge. Which is to assemble a team of 200 top scientists, from India and elsewhere, to work on newer and more efficient ways, and getting customers and partners to come to the city to work with the team.

Mysuru, you’d think, is right. The tag of India’s cleanest city and close to Kerala, the country’s main rubber producing state. Also, a salubrious climate, bettered only by the state capital in Bengaluru.

However, the second largest city of Karnataka in size has an airport not served by any airline. The last commercial flight was in 2014. The train trip from Bengaluru is three hours, except for the Shatabdi that takes two hours. By road, a bus trip of 140 km from the capital takes a little over three hours. So, for someone coming to the city from Delhi or Mumbai, the journey takes a day.

“The biggest hurdle for us to get people over here is connectivity. They lose one day just by travelling,” says Shenoy. “Every other day, the conversation comes to someone not wanting to travel because it takes longer to reach here.”

In January, Venu Srinivasan, chairman and managing director of TVS Motor Co, also having a factory in Mysuru, made a plea, ahead of a global investors’ meet, that the journey time to the city be cut to one hour. This, he said, would make Mysuru an attractive investment place and help decongest Bengaluru.

Mysuru has a population 1.24 million, around an eighth of the people count in Bengaluru.

“For a large state, the population should be distributed. In Karnataka, it is not so. It has one large city and no other city is even half way to it,” says Ashwin Mahesh, who runs the Centre for Public Problem Solving, which focuses on making cities for better living. “Ideally, a second city should have a population 40-50 per cent of what the largest city has. Progressively, the gap is going to be worse.”

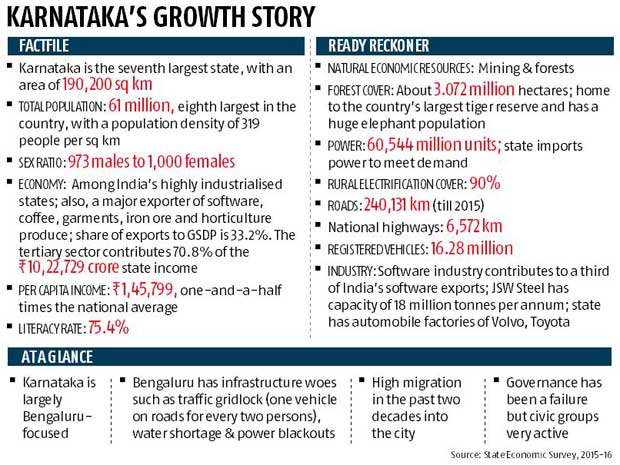

At Rs 1,45,799, the state’s per capita income in 2015-16 was one-and-a-half times the national average, due to a focus on information technology. Since 1993-94, the proportion of exports in gross state domestic product (GSDP) has risen by nearly five times, to 33.2 per cent in 2014-15. It was 7.36 per cent in 1993-94, according to the state economic survey for 2015-16. Software accounted for 61.8 per cent of Karnataka’s exports, of Rs 3,13,570 crore.

ALSO READ: Jharkhand building land bank to woo industry

The bulk of Karnataka’s economic activity is in Bengaluru; the city contributes a third of India’s software export. The Bengaluru urban district has 38.7 per cent of the state’s population and contributes 33.6 per cent to GSDP. The next large contributor is Dakshina Kannada, with 5.8 per cent.

Bengaluru, with a population of 11 million, had 6.1 million vehicles as of March 2016, with average speeds of 10 kmph on most roads. Jokes on the plight of vehicle users stuck for hours at junctions are part of urban folklore.

The first phase of the Metro rail is set to be completed by November, which authorities expect would take 500,000 people a day. The city has the highest number of buses on road. The 100-odd lakes that are still there are either polluted or encroached on. Groundwater levels are at a historic low and there are massive violations of the law in construction of buildings. The city is among the most polluted in the country.

More From This Section

Still, Bengaluru is India’s leading job generator. More qualified professionals are moving here than to any other city, according to a study by LinkedIn. It also has an active civic society, trying to bring improvement in governance.

ALSO READ: Andhra races to be in Gujarat's shoes

For three years, the state government had ignored cries for improving the infrastructure. With the BJP appointing B S Yeddyurappa to campaign for the legislative Assembly elections two years from now, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has begun focusing on the city. He announced Rs 7,200 crore in spending on infrastructure projects, including Rs 1,300 crore for an elevated road to connect the city centre to the highway leading to the airport.

Rajya Sabha member Rajeev Chandrasekhar has called the projects political and contractor-driven than benefiting the citizens. “It is not part of an overall plan. You say of the Rs 7,200 crore, Rs 1,800 crore is for an elevated road and this will have to be completed two years before elections. The government wants to spend money desperately,” asks Chandrasekhar. “There is no public consultation. It is ad hoc.”

He called for a multi-year perspective plan for transportation than ad hoc projects that aggravate commuting problems. Mahesh also calls for a comprehensive plan. “They don’t have a holistic thinking when they talk of infrastructure. It should include footpaths, cycling paths, bus shelters,” he says. “The Rs 1,800 crore for six km could be used to buy 4,000 buses that can carry three million people a day.”

Siddaramaiah has formed a Vision Group for Bengaluru. It has Infosys co-founder N R Narayana Murthy, Flipkart’s Sachin Bansal, Biocon chief Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw and Ramesh Ramanathan, founder of Janaagraha, a non-profit that works on improving urban governance.

Shaw, in a recent interview, said the group’s focus would not only be to suggest short-term action plans but look at the long term, on how the city can be sustained for the decades to come. Flipkart’s Bansal has raised concerns of infrastructure that would affect Bengaluru as an investment destination.

“On infrastructure, it takes time for implementation. The government is at it - elevated corridor, Metro second phase. Things are happening, we have created speed in implementation and are working on it,” says R V Deshpande, the state’s industries minister.

)