Microfinance institutions, or MFIs, have come a long way since the 2010 crisis in Andhra Pradesh that temporarily grounded SKS Microfinance, the leading micro-lender of that time and the only one listed on the stock market. In the last 18 months, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which sees itself as a conservative regulator, has granted bank licences to nine MFIs: while Bandhan got a universal banking licence in April 2014, eight micro-lenders this month received the nod to operate small finance banks.

Clearly, the regulator has noted the work done by MFIs in extending credit to the last mile where many established banks failed to reach. Notwithstanding the Andhra Pradesh crisis that was triggered by rising debt stress among clients forcing many of them to commit suicide, MFIs flourished in many states and showed that theirs is a viable business model. This in turn attracted investors who took significant equity stakes in these entities. The International Finance Corporation, the private lending arm of the World Bank, for instance, has invested in many of these small finance banks that have received the regulator's approval, apart from being an investor in Bandhan.

"The microfinance industry has matured into a formal lending channel over the years because the business model has been robust to focus on the unbanked, the rates are fixed and there is a code of conduct that has to be followed," says Disha Group Director Rajeev Yadav."Moreover, microfinance players have been focusing on financial inclusion, which was bound to attract RBI's attention."

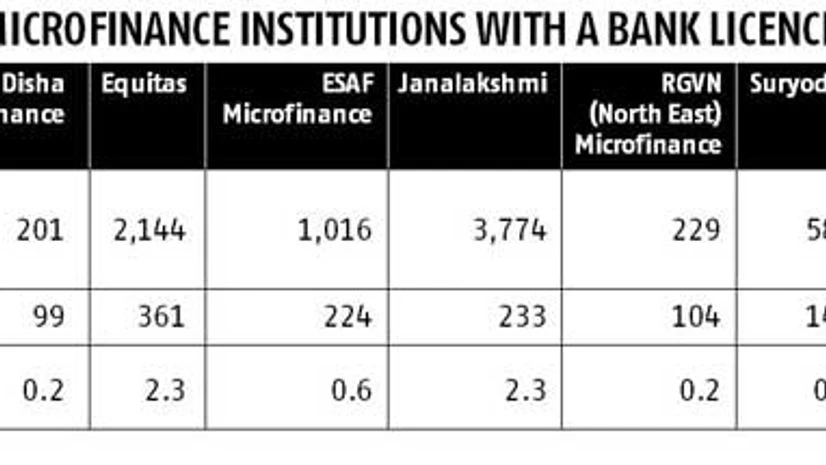

Disha Microfin is an Ahmedabad-based micro-lender that has received RBI's in-principle approval to start a small finance bank. With asset under management of Rs 200 crore, it has operations across four states: Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. The Andhra Pradesh crisis also made MFIs improve their corporate governance practices, which is reflected in the low promoter's stake in most of these entities; in some cases, it is around 10 per cent.

"Since 2010, RBI has in consultation with the industry introduced several regulations to protect customers," says Samit Ghosh, CEO & MD, Ujjivan, another MFI that has received a small finance bank licence.

Helpful measures

"In any fast-growing industry, meaningful regulation is needed to ensure that growth continues, and that is what we saw happen in 2011 after the crisis. There were clear guidelines on pricing and scope of business, and these have helped the microfinance industry grow since then," says R Baskar Babu, CEO of Suryoday Micro Finance which has also got a licence to start a small finance bank."Most MFIs, especially the ones that have got the licence, are run by professionals."

The micro-lender is present in seven states, operating through 164 branches and serving over 600,000 customers. Its major investors include DWM, Aavishkaar Goodwell, IFC, Lok Capital, HDFC and HDFC Life.

While most of the lenders have survived the Andhra Pradesh crisis, including SKS Microfinance, the regulator, it seems, is still treading with caution. Despite huge expectations that it would get a licence, SKS Microfinance failed to obtain one. Its stock plunged 15.5 per cent on September 18 after its name did not figure in the list. Analysts, however, say that not getting a small finance bank licence is not end of the road for SKS Microfinance.

"SKS Microfinance probably enjoys 300-400 basis points funding cost benefit over the smaller MFIs that have won the small bank licence. We believe the benefits from bank conversion for MFIs, if at all, are not immediate but will accrue over the long term (5+ years in most cases). Thus, we do not feel SKS Microfinance's competitive positioning would be negatively impacted in any material way in the foreseeable future," Credit Suisse said in a note to its clients.

However, experts believe conversion to a bank is the only way that NBFCs (MFIs too are a category of NBFC) can survive because it will give them access to low-cost savings and current account deposits. Banks typically pay 4 per cent interest on savings bank deposits. (Some private sector banks pays more, up to 6-7 per cent). MFIs depend mostly on banks for their resources, and their cost of funds is therefore upward of 12 per cent.

Even if small finance banks have to maintain statutory liquidity ratio, or SLR, and cash reserve ratio, or CRR, unlike NBFCs, their overall cost of funds will be lower than an MFI. "Our calculation suggests that even after adjusting for SLR and CRR, the cost of funds for the small finance banks will be 100-150 basis points below NBFCs and MFIs. In our base case, we assume a very low savings account proportion of 5 per cent of liabilities, retail term deposits of 15 per cent and the rest through bulk deposits or borrowings; this translates into a 10.1 per cent cost of funds," Religare Securities said in a report.

Small finance banks whose prime responsibility will be to provide savings instruments to the financially underserved and extend credit facility to small farmers and small businesses can become successful if they manage three parameters well: risk management, cost management (traditionally, an MFI's operational costs are high), and quality of customer services through adoption of technology.

Things will improve further for the MFIs that have received the licence for small finance banks if they can next convert themselves into universal banks. This conversion will not be automatic but will need RBI's approval which will depend on their track record.

"In our view, this is a giant leap towards financial inclusion; as these small banks will be able to serve the underserved within the ambit of stable regulatory framework. Moreover, in due course, these applicants would be considered for universal banking licence if they are successfully able to build a profitable business model and achieve the desired objectives," Motilal Oswal Securities said in a report.

)