Muhammad Ali, earlier called Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr, was born in Louisville on January 17, 1942, into a family of strivers that included teachers, musicians and craftsmen.

Ali's mother, Odessa, was a cook and a house cleaner, his father a sign painter and a church muralist who blamed discrimination for his failure to become a recognised artist. Violent and often drunk, Clay Sr filled the heads of Cassius and his younger brother, Rudolph (later Rahman Ali), with the teachings of the 20th-century black separatist Marcus Garvey and a refrain that would become Ali's - "I am the greatest."

Beyond his father's teachings, Ali traced his racial and political identity to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old from Chicago who was believed to have flirted with a white woman on a visit to Mississippi. Clay was about the same age as Till, and the photographs of the brutalised dead youth haunted him, he said.

Clay started to box at 12, after his new $60 red Schwinn bicycle was stolen off a downtown street. He reported the theft to Joe Martin, a police officer who ran a boxing gym. When Clay boasted what he would do to the thief when he caught him, Martin suggested that he first learn how to punch properly. Clay was quick, dedicated and gifted at publicising a youth boxing show, "Tomorrow's Champions," on local television. He was soon its star.

For all his ambition and willingness to work hard, education - public and segregated - eluded him. The only subjects in which he received satisfactory grades were art and gym, his high school reported years later. Already an amateur boxing champion, he graduated 376th in a class of 391. He was never taught to read properly; years later he confided that he had never read a book, neither the ones on which he collaborated nor even the Quran, although he said he had reread certain passages dozens of times. He memorised his poems and speeches, laboriously printing them out over and over.

In boxing he found boundaries, discipline and stable guidance. Martin, who was white, trained him for six years, although historical revisionism later gave more credit to Fred Stoner, a black trainer in the Smoketown neighbourhood. It was Martin who persuaded Clay to "gamble your life" and go to Rome with the 1960 Olympic team despite his almost pathological fear of flying.

Clay won the Olympic light-heavyweight title and came home a professional contender. In Rome, Clay was everything the sports diplomats could have hoped for - a handsome, charismatic and black glad-hander. When a Russian reporter asked him about racial prejudice, Clay ordered him to "tell your readers we got qualified people working on that, and I'm not worried about the outcome." "To me, the USA is still the best country in the world, counting yours," he added. "It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain't fighting alligators and living in a mud hut."

Ali would later cringe at that quotation, especially when journalists harked back to it as proof that a merry man-child had been misguided into becoming a hateful militant.

Of course, after the Rome Games, few journalists followed Clay home to Louisville, where he was publicly referred to as "the Olympic nigger" and denied service at many downtown restaurants. After one such rejection, the story goes, he hurled his gold medal into the Ohio River. But Clay, and later Ali, gave different accounts of that act, and according to Thomas Hauser, author of the oral history Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Clay had simply lost the medal.

Clay turned professional by signing a six-year contract with 11 local white millionaires. The so-called Louisville Sponsoring Group supported him while he was groomed in Miami. At a mosque there, Clay was introduced to the Nation of Islam, known to the news media as "Black Muslims." Years later, after leaving the group and converting to orthodox Islam, Ali gave the Nation of Islam credit for offering African-Americans a black-is-beautiful message at a time of low self-esteem and persecution.

Title and transformation

Clay enjoyed early success against prudently chosen opponents. His outrageous predictions, usually in rhyme - "This is no jive, Cooper will go in five" - put off many older sportswriters, especially since most of the predictions came true. (The Englishman Henry Cooper did go down in the fifth round at Wembley Stadium in 1963, after he had staggered Clay in the fourth.) The reporters' ideal of a boxer was Joe Louis. But they still wrote about Clay. Younger sportswriters, raised in an age of Andy Warhol, happenings and the "put on," were delighted by the hype and by Clay's friendly accessibility.

In 1963, at 21, after only 15 professional fights, he was on the cover of Time magazine. The winking quality of the prose - "Cassius Clay is Hercules, struggling through the twelve labours. He is Jason, chasing the Golden Fleece" - reinforced the assumption that he was just another boxer being sacrificed to the box office's lust for fresh meat. It was feared he would be seriously injured by the baleful slugger Liston, a 7-to-1 betting favourite to retain his title in Miami Beach, Florida, on February 25, 1964. But Clay was joyously comic. Encouraged by his assistant trainer and "spiritual adviser," Drew Brown, known as Bundini, Clay mocked Liston as the "big ugly bear" and chanted a battle cry: "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, rumble, young man, rumble."

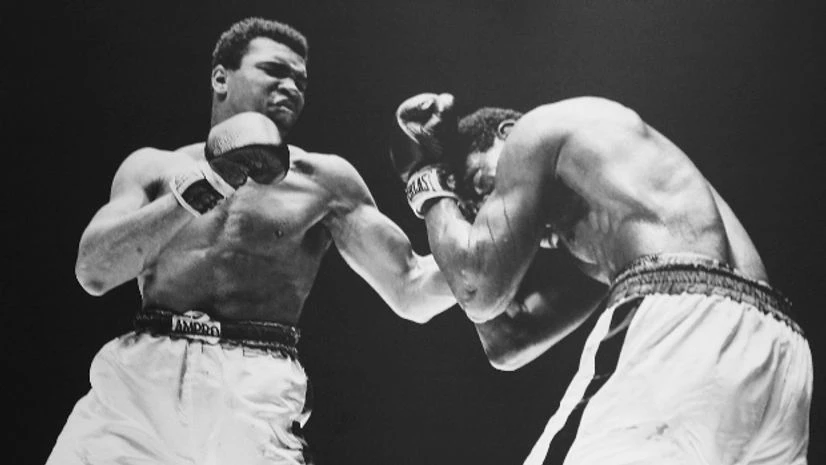

To the shock of the crowd, Clay, taller and broader than Liston at 6 feet 3 inches and 210 pounds and much faster, took immediate control of the fight. He danced away from Liston's vaunted left hook and peppered his face with jabs, opening a cut over his left eye. Later, Clay, the new champion, capered along the ring apron, shouting at the press: "Eat your words! I shook up the world! I'm king of the world!"

The next morning, a calm Clay affirmed his rumoured membership in the Nation of Islam. He would be Cassius X. (A few weeks later he became Muhammad Ali, which he said meant "Worthy of all praise most high.") That day he harangued his audience with a preview of what would, over the next few years, become a series of longer and more detailed lectures about religion and race. This one was about, as he put it, "staying with your own kind." The only prominent leader to send Ali a telegram of congratulations was the Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

|

Ali on not fighting in Vietnam Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality. If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.

—Muhammad Ali |

Refusing to be drafted

On February 17, 1966, a day already roiled by the Senate's televised hearings on the war in Vietnam, Ali learned that he had been reclassified 1A by his Louisville selective service board. He had originally been disqualified by a substandard score on a mental aptitude test. But a subsequent lowering of criteria made him eligible to go to war. The timing, however, was suspicious to some; the contract with the Louisville millionaires had run out, and Nation members were taking over as Ali's managers and promoters.

"Why me?" Ali said when reporters swarmed around his rented Miami cottage to ask about his new draft status. "I buy a lot of bullets, at least three jet bombers a year, and pay the salary of 50,000 fighting men with the money they take from me after my fights." But as the reporters continued to press him with questions about the war, the geography of Asia and his thoughts about killing Vietcong, he snapped, "I ain't got nothing against them Vietcong."

The remark was front-page news around the world. In America, the news media's response was mostly unfavourable, if not hostile. The sports columnist Red Smith of The New York Herald Tribune wrote, "Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius makes himself as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war." Most of the press refused to refer to Ali by his new name. When two black contenders, Floyd Patterson and Ernie Terrell, insisted on calling him Cassius Clay, Ali taunted them in the ring as he delivered savage beatings.

On April 28, 1967, Ali refused to be drafted and requested conscientious-objector status. He was immediately stripped of his title by boxing commissions around the country. Several months later he was convicted of draft evasion, a verdict he appealed. He did not fight again until he was almost 29, losing three and a half years of his athletic prime.

They were years of personal and intellectual growth as Ali supported himself on the college lecture circuit, offering medleys of Muslim dogma and boxing verse. In the question-and-answer sessions that followed, Ali was forced to explain his religion, his Vietnam stand and his opposition (unpopular on most campuses) to marijuana and interracial dating. Now the "onliest boxer in history that people asked questions like a senator" developed coherent answers.

As Ali's draft-evasion case made its way to the United States Supreme Court, he returned to the ring on October 26, 1970, through the efforts of black politicians in Atlanta. The fight, which ended with a quick knockout of the white contender Jerry Quarry, was only a tuneup for Ali's anticipated showdown with Frazier, the new champion. But it was a night of glamour and history as Coretta Scott King, Bill Cosby, Diana Ross, the Rev Jesse Jackson and Sidney Poitier turned out to honour Ali. The Rev Ralph Abernathy presented him with the annual Dr King award, calling him "the March on Washington all in two fists."

"The Fight," as the Madison Square Garden bout with Frazier on March 8, 1971, was billed, lived up to expectations as an epic match. With Norman Mailer ringside taking notes for a book and Frank Sinatra shooting pictures for Life magazine, Ali stood toe to toe with Frazier and slugged it out as if determined to prove that he had "heart," that he could stand up to punishment. Frazier won a 15-round decision. Both men suffered noticeable physical damage.

To Ali's boosters, the money he had lost standing up for his principles and the beating he had taken from Frazier proved his sincerity. To his critics, the bloody redemption meant he had finally grown up. The Supreme Court also took a positive view. On June 28, 1971, it unanimously reversed a lower court decision and granted Ali his conscientious-objector status.

In recent years, Parkinson's disease and spinal stenosis limited Ali's mobility and ability to communicate. He rarely did TV interviews, his wife said, because he no longer liked the way he looked on camera. "But he loved the adoration of crowds," she said. "Even though he became vulnerable in ways he couldn't control, he never lost his childlike innocence, his sunny, positive nature. Jokes and pranks and magic tricks. He wanted to entertain people, to make them happy."

©2016 The New York Times News Service

HIS WORDS ALSO PACKED A PUNCH

"Impossible is not a fact. It's an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It's a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing."

***

"Hating people because of their colour is wrong. And it doesn't matter which colour does the hating. It's just plain wrong."

***

"I should be a postage stamp. That's the only way I'll ever get licked."

***

"I hated every minute of training, but I said, 'Don't quit. Suffer now and live the rest of your life as a champion.'"

***

"A man who views the world the same at 50 as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life."

***

"Only a man who knows what it is like to be defeated can reach down to the bottom of his soul and come up with the extra ounce of power it takes to win when the match is even."

***

"A man who has no imagination has no wings."

***

"If they can make penicillin out of moldy bread, they can sure make something out of you."

***

"At home I am a nice guy: but I don't want the world to know. Humble people, I've found, don't get very far."

***

"I am the astronaut of boxing. Joe Louis and Dempsey were just jet pilots. I'm in a world of my own."

***

"I've wrestled with alligators. I've tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning. And throw thunder in jail."

|

THE WORLD SALUTES Ali, Frazier & Foreman, we were one guy. A part of me slipped away, "the greatest piece" - Muhammad Ali." - George Foreman, who Ali beat in the "Rumble in the Jungle" fight in Kinshasa, Zaire, in 1974. Ali's "rope-a-dope" strategy tired the unbeaten Foreman in the 80-degree heat, allowing him to force a stoppage in the eighth round. "Boxing benefitted from Muhammad Ali's talents but not as much as mankind benefitted from his humanity." - Manny Pacquiao, boxer "There will never be another Muhammad Ali. The black community all around the world, black people all around the world, needed him. He was the voice for us. He's the voice for me to be where I'm at today." - Floyd Mayweather, former American boxer "Muhammad Ali was The Greatest. Period. Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world was better for it. We are all better for it." - Barack Obama, US President "We watched him grow from the brash self-confidence of youth and success into a manhood full of religious and political convictions that led him to make tough choices and live with the consequences. Along the way we saw him courageous in the ring, inspiring to the young, compassionate to those in need, and strong and good-humoured in bearing the burden of his own health challenges." - Bill Clinton, former US president "Muhammad Ali was not just a champion in the ring - he was a champion of civil rights, and a role model for so many people." - David Cameron, British prime minister My hero since childhood. I always had a wish to meet you some day but now it will never happen. RIP "The Greatest" - Sachin Tendulkar, cricketer RIP Muhammad Ali...we will miss your spirit and humanity. You were shunned,excoriated and jailed for the same reason that made you a hero." - Martina Navratilova, former tennis player He was an absolute collosus and made the biggest impact in sport, and possibly outside it, in my lifetime - Sebastian Coe, former middle-distance runner |

)