Rajat Gupta disagrees with US SC's insider trading ruling

The court ruled that sharing corporate secrets is illegal even if the tipsters did not receive anything in return

)

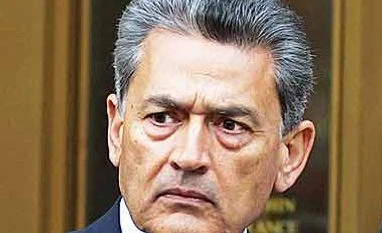

Rajat Kumar Gupta

India-born former Goldman Sachs director Rajat Gupta, who is arguing in appeal that the government lacked evidence to show he "received even a penny" for passing insider information, has disagreed with a US Supreme Court ruling that sharing corporate secrets is illegal even if the tipsters did not receive anything in return.

In a landmark ruling earlier this month, relating to the insider trading conviction of Illinois resident Bassam Yacoub Salman, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that sharing corporate secrets with friends or relatives is illegal even if the insider providing the tip doesn't receive anything of value in return.

Sixty-eight-year-old Gupta is a free man now after completing a prison term on insider trading charges but is not giving up his legal battle to overturn his conviction, arguing that he served two years in jail for conduct that is not criminal even though the government lacked evidence to show he "received even a penny" for passing confidential boardroom information to now jailed hedge-fund manager Raj Rajaratnam.

In May, Gupta's team of lawyers had argued in papers before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals that the judgement of the Manhattan district court finding Gupta guilty of insider trading "should be reversed" and his "conviction should be vacated".

Gupta's appeal comes on the back of a ruling by the Manhattan appeals court that for an insider trading conviction prosecutors must show that a defendant received a personal benefit for passing illegal tips. Gupta's lawyers have cited the ruling that led to the reversal of insider convictions of hedge-fund managers Todd Newman and Anthony Chiasson in December, 2014.

Also Read

In fresh court papers, following the verdict in Salman's case, Gupta said there is "a fatal inconsistency" and he was "substantially prejudiced by the invalid theory of benefit pursued at trial; and that his entitlement to relief is in no way affected" by the verdict in the Salman case.

"The issue on this appeal is whether the government's benefit theory (that Gupta tipped to maintain a good relationship with Rajaratnam), and the district court's instruction that the benefit could be modest, intangible and non-financial, are fatally inconsistent with Newman's quid pro quo requirement: an exchange of a tip for a benefit that is 'objective, consequential, and at least potentially pecuniary'," Gupta's lawyers said in court papers.

The government said Gupta's appeal lacked merit even under the Newman ruling and the Salman verdict "confirms the validity of the District Court's jury instructions and thus defeats Gupta's claim of error at the outset".

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Dec 21 2016 | 12:04 PM IST