Had England's Lever Brothers not insisted on inserting the letter 'L' in the name, then perhaps, India's most loved vanaspati ghee would have been called Dada.

Dada was actually the name of the Dutch company that imported vanaspati ghee into India in the 1930s as a cheap substitute for desi ghee or clarified butter, prepared from cow's milk. Ghee was an expensive product and something that was used sparingly in Indian households - over weekends or when preparing a delicacy or a dessert. Vanaspati ghee, on the other hand, was a type of vegetable shortening made up of hydrogenated or highly saturated vegetable oil and made to mimic desi ghee.

Lever Brothers, now Unilever (Hindustan Unilever in India), knew there was a market for a substitute for desi ghee, since many Indians could barely afford ghee. The maker of home and personal care products had already entered food production by the early 20th century in Europe and was looking to produce vanaspati ghee in India. It had also incorporated a company called Hindustan Vanaspati Manufacturing Company in 1931 for the purpose.

Sensing an opportunity to make inroads into the domestic vanaspati ghee market, Lever bought the rights to make Dada in India. There was one pre-condition to the sale: The name Dada had to be retained. Of course, Lever thought otherwise. Its stamp of ownership had to be there somewhere on the product. So the astute consumer goods marketer came up with a solution: The letter L standing for Lever was put right in the middle. Thus, was born Dalda, which was introduced in 1937.

But, Lever's work was far from over. The Indian public was far from convinced there could be any substitute for ghee. Ghee typically lends its taste and aroma when used as a cooking medium or even when sprinkled over food.

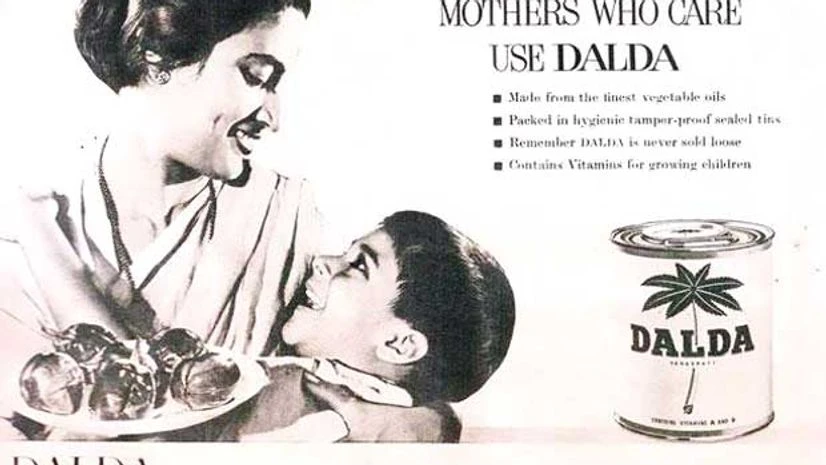

That is where Lever's ad agency, Lintas, came into the picture. Harvey Duncan, who handled the Dalda account at Lintas, created what was India's first multi-media advertising campaign in 1939. There was a short film to screen in theatres, a round tin-shaped van to roam the streets, print ads for the literate, stalls to spur sampling and detailed leaflets for distribution as part of the ad blitzkrieg.

Dalda began standing out not just for the enveloping campaigning, but also because of the tins sporting the distinct green palm tree logo on yellow. Lever transported these distinctive tins via its distribution network across the length and breadth of the country. There were different pack sizes targeting different consumers: A large square tin for institutional users such as hotels and restaurants and smaller round tins for in-home consumption. Lever left no stone unturned to promote Dalda, pitching it as a credible alternative to ghee.

Ad historians say that for the first 25-30 years of its existence, Dalda had no competition from local and international edible oil makers. Dalda quite literally had a monopoly over the market till the 1980s.

Dalda rode over the initial controversies, such as the one in the 1950s, which called for a ban on Dalda, because it was a "falsehood" - a product that imitated desi ghee, but was not the real deal. In other words, critics argued that Dalda was an adulterated form of desi ghee, harmful for health.

The Prime Minister then, Jawaharlal Nehru, called for a nationwide opinion poll, which proved inconclusive. A committee was set up by the government to suggest ways to prevent adulteration of ghee. But nothing came of it.

Of course, years later Dalda had to contend with another controversy that said it contained animal fat - this was in the 1990s. By then, Dalda had competition from "clear oils" or refined vegetable oils such as groundnut (Postman), mustard, safflower (Saffola), sunflower (Sundrop) and palm oil (Palmolein), among others.

These were considered a healthier option to vanaspati ghee. Dalda was losing its hold over Indian kitchens, and by 2003 had been offloaded by HUL to American agri and food major Bunge for reportedly under Rs 100 crore.

For Bunge, the Dalda acquisition was the big leap it was seeking in the edible oil market. There were false starts, partly because of the vanaspati ghee legacy. As Boke says,

"We first launched an edible oil range under Dalda in 2007. We did this under the tagline 'Husband's Choice'. But we soon realised that it wasn't clicking in the marketplace. In 2013, we relaunched the range under the tagline 'Dabba khali, peth full' (Tiffin box empty, stomach full) and did extensive below-the-line activities besides above-the-line campaigns, to promote this new positioning of the brand."

If Lever had a clean slate to build Dalda on, Bunge has to lay a part of Dalda's legacy to rest that was synonymous with vanaspati ghee, and give it a fresh lease of life.

)