In 2014, hedge funds focused on India were a shining symbol of the bull market sparked by Narendra Modi's rise to power. This year, they serve as a reminder of the limitations of investing in Asia's third-largest economy.

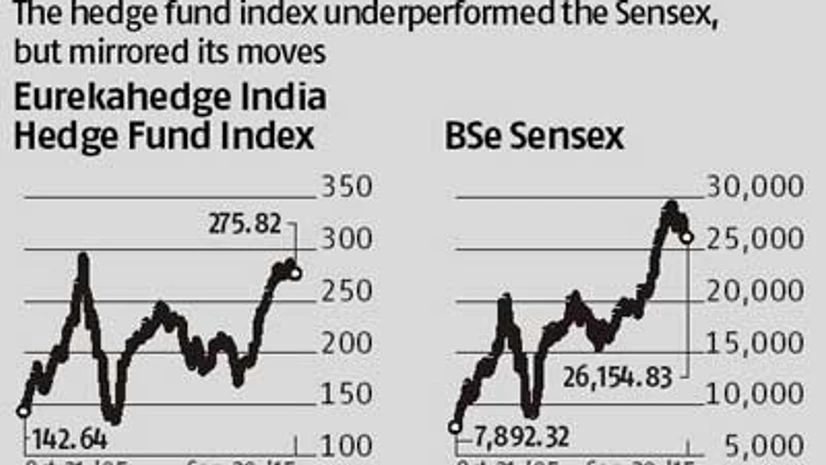

After beating peers in all other markets last year with a 39 per cent advance, India hedge funds posted the third-lowest returns in the Asia-Pacific region in the first nine months of 2015, rising just 2.9 per cent, Eurekahedge Pte estimates.

The abrupt reversal in performance underscores a wider issue dogging investors seeking returns in bull and bear markets alike: hedge funds in India track local stocks more closely than in any of the world's major markets. That pattern looks likely to persist because of a scarcity of tools for profiting when equities fall, such selling shares short.

"Shorting is a very important tool for an investor," said Sumeet Nagar, a Mumbai-based managing director at Malabar Investment Advisors, which runs the $250-million Malabar India Fund. "But the set of opportunities is limited, so the criticism is valid that you don't have that many short options in India."

The beta, a measure of how closely returns track the market, is 0.77 for India's equity hedge funds, according to Eurekahedge. That's far higher than the 0.49 for the whole of Asia, 0.51 for North America and 0.38 for Europe. A beta of one means returns move perfectly in tandem with the market.

Tracking the wider market was a profitable strategy last year, when the benchmark S&P BSE Sensex Index rallied 30 per cent. The Sensex declined 0.5 per cent this year through October 26.

The ability to short - the practice of selling borrowed shares with the aim of buying them back later at a lower price - isn't guaranteed to produce profits. The equity long-short Farringdon Alpha One Fund, based in Amsterdam and Copenhagen, fell 1.2 per cent last month through September 15, according to a document obtained by Bloomberg. And Glenview Capital Management, the US hedge fund firm led by Larry Robbins, lost 12.4 per cent in its main fund the same month as bets on health-care companies suffered.

Yet, shorting gives managers a greater chance of weathering down markets, and to profit from making bearish bets on stocks or other assets they consider overvalued. However, in India it is rarely done because of higher margin requirements and because regulatory reasons limit the availability of stocks which brokers can lend.

The use of futures and options is also limited, because futures on just 160 of the more than 5,000 stocks listed in India can be traded on the country's stock exchanges, in addition to futures on the benchmark indices.

Roshan Padamadan, manager of the Luminance Global Fund said the country's middle class tends to buy more gold and real estate, "due to the higher perceived safety and also because it's easier to park unreported wealth in those assets," he said.

Over the last 100 days, stocks listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange were traded on average 59,000 times per day, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That's much less than the 372,000 trades per share on the New York Stock Exchange and the 797,000 trades on the London Stock Exchange.

Shorting futures

Malabar's Nagar said his firm finds it difficult to wager against small and mid-sized stocks because there is a liquid market in futures and options only for the largest companies traded in India. When Malabar wants to hedge against potential declines in the wider market, it shorts index futures, he said.

India-focused hedge funds are also more exposed to stocks than managers in other markets that also invest in bonds, currencies and other assets. Of the 82 funds making up the $3.5 billion hedge fund industry in India, 83 per cent invest only in equities. That compares with 45 percent for all of Asia, 34 per cent in North America and 35 per cent in Europe, according to Eurekahedge.

The industry's dependence on the stock market was on display in August, when hedge funds dropped an average 4.4 per cent for the worst performance in almost two years, as the Sensex slumped 6.5 per cent.

Samir Arora, Singapore-based manager of the Helios Strategic Fund, said the volatile nature of India's market means authorities should do more to bring it more closely in line with international standards by easing restrictions on short-selling.

Arora said his fund takes bearish bets mainly by selling futures on individual stocks.

"The more volatile the market is, the more important is downside protection to achieve higher long-term returns," said Arora.

)