Is India an open or closed economy? More than 20 years after the repudiation of the licence quota raj model by the Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh reforms initiated in 1991, the answer to that question should be clear. But apparently not. The answer depends upon whether "openness" is measured by trade policy or by actual trade outcomes. Consider each.

In contrast, barriers are very high (both in absolute terms and relative to other countries) in services. Graph 2, from World Bank researchers (Borchert, Gootiz, and Mattoo, 2012), provides a sense of magnitudes. It plots a country's services barriers (on a scale of 0 to 100 on the vertical axis, with a higher number depicting greater restrictiveness) against its level of development (on the horizontal axis). The downward sloping line suggests that, on average, barriers tend to be greater in poorer countries.

The key points are that: first, India's overall barriers in services (denoted by the "IND" symbol) are among the highest in the world (surpassed only by Zimbabwe) and nearly four-five times greater than those in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries; and, second, they are also very high for India's level of development because India is well above the line.

The usual caveats, that all such measurements are incomplete (because they do not fully capture regulatory barriers) and imperfect, should not be overlooked. Subject to them, however, the conclusion is that compared to the rest of the world, India's manufacturing sector faces modest levels of protection, and the services sector faces extremely high levels of protection, resulting in an overall trade regime that is quite protectionist.

Also Read

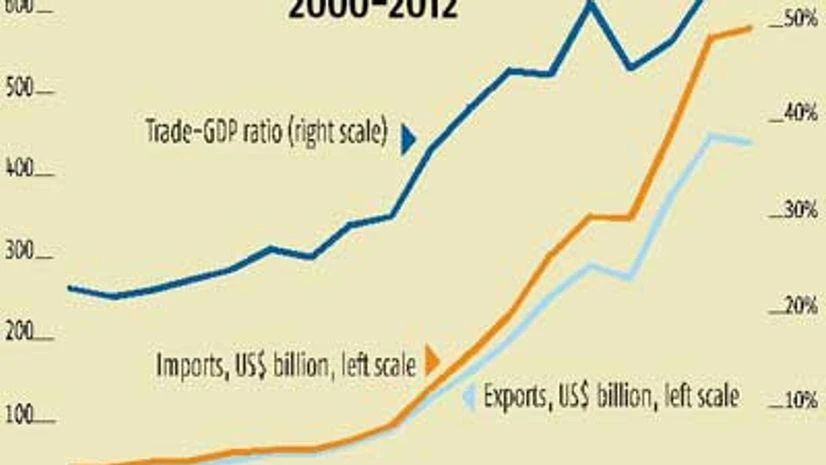

But is this 53 per cent a small or large number compared with other countries? A geography-based view of trade highlights an overlooked fact, namely that large countries tend to trade less than small countries. Being large makes the cost of trading with the outside world relative to trading within the country very high. The opposite is true for small countries: lacking an internal market, their costs of trading with the world are relatively small and hence they tend to have higher trade-to-GDP ratios.

But in a comparative sense, what is interesting is that India is above the line, indicating that for its size, it trades more than the typical country does. Comparisons based on trade in goods indicate that India is a normal trader. But comparisons based on overall trade (goods and services), shown in Graph 4, indicate that India is an over-trader, sometimes significantly so. A more formal (but simple) regression analysis confirms that India's overall trade is about 25 per cent greater than it should be for a country of its size and economic development.

Unsurprisingly, countries such as China, and especially Malaysia, Thailand, Korea and Germany, are large traders (they are well above the line in Graph 4). It is countries such as Brazil, Japan and the US (well below the line) that are unusually low traders given their size.

So, when India's trading partners complain about the restrictiveness of the country's trade regime, they are both right and wrong. It is closed in trade policy terms but open in terms of trade outcomes. Joan Robinson probably had some lofty, metaphysical conception when she observed that everything and its opposite was true about India. That observation applies more mundanely to India's trade regime too.

The writer is senior fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics and Centre for Global Development

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)