The Eleventh Five Year Plan, which ran from 2007 to 2012, had a clear focus on closing the gap in India's infrastructure needs. It had estimated a $500-billion target spend on infrastructure covering key areas such as, power, airport, roads and ports among others and recognised that to do this, private sector involvement was necessary.

Given that India's gross domestic product in 2007 was just around $1 trillion, it was abundantly clear that the government did not have the resources to provide for the entire infrastructure needs of India. The gap was not just with its financial resources but also related to the skills and expertise required to build out the different elements of the necessary infrastructure. The Plan targeted 37 per cent of infrastructure spend to come from the private sector. Thus, India needed to embark on the somewhat complex process of creating a robust, fair and efficient manner of involving the private sector in the infrastructure build-out, given that many areas of infrastructure create monopoly assets that naturally cannot be simply given to the private sector to own. This led to the requirement of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the build-out of infrastructure.

The global experience around PPP highlights the complexity of such contracts - they are always intricate, require complex bidding terms and need inter-temporal pricing and often renegotiation during the pendency of the contract. An easy example by which to illustrate this point would be spectrum allocation. Should spectrum be allocated to the highest bidder via an auction, leading to an increase in the price of telecom services, or allocated by a method that can foster the spread and take-up of telecom services by a bulk of the population? The agencies that were to regulate these infrastructure PPPs had little experience and the volume of such projects was quite large, causing an overload on them.

Further, infrastructure projects also touch the heart of India's political economy and political fund-raising. They always involve use of land, rights and the environment! I have written elsewhere about the costs of running India's democracy and the inability of official forms of funding to suffice. Thus, the mix of complex PPPs involving spectrum, land and environment clearances, regulatory agency overload, and plain corruption led to a very high portion of these projects being stuck for want of clearances.

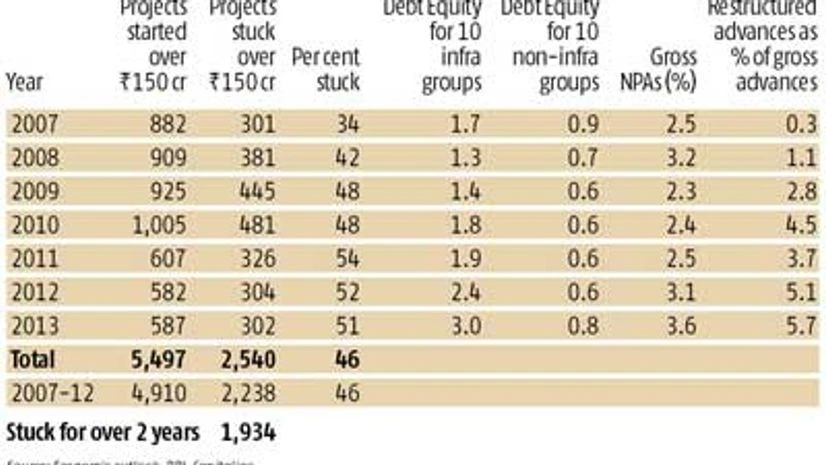

During the Eleventh Plan, 4,910 capital projects of over Rs 150 crore came up of which 2,238 projects, or 46 per cent, were stuck for want of some clearance or the other. The sensational Comptroller and Auditor General's report on spectrum allocation in 2010 alleging Rs 1,76,000 crore was foregone by government, increased public scrutiny and led to a further slowdown, some would argue paralysis, in decision-making.

The consequence of capital projects not coming on stream led to a clear set of consequences on the balance sheets of infrastructure companies and the banks lending to them. The statistics are quite telling. If we studied the debt:equity ratios of infrastructure conglomerates between 2008 and 2013, we see them rise from 1.3 in 2008 to three in 2013. In fact, between 2011 and 2013, India's incremental capital output ratio rose from 3.75 to 7.75 and for some sectors like power had gone up to over 16.

During the same period, banks that were lending to infrastructure also started to feel the pain. Given that the bulk of the balance sheet business in India is done by public sector banks, about 80 per cent of the lending was on their balance sheets. This was not one bank lending poorly to one company but all banks participating in certain sectors facing the pain. Gross non-performing assets (NPAs) after a decade of decline went up to 3.6 per cent, and 5.7 per cent of the assets had to be restructured via corporate debt restructurings. Restructured assets told a very clear tale - steel, power, telecom, infrastructure formed more than 50 per cent of bank-restructured assets. Currently 1,934 projects are stuck for over two years for want of some government clearance - mostly land, environment or mining.

Since the return of P Chidambaram to the finance ministry there has been a strong attempt to clear stuck projects but what has not received any attention is the financial situation of these projects. The promoters' equity in these projects has been wiped out and banks are holding the can. One can argue over whether or not the projects had been gold-plated and whether the promoters had actually put in all the equity they claim, but the interest costs on these stuck projects have mounted to the extent that these projects are currently not viable. It is not that these projects are not needed or that the lending originally was necessarily poor. The banks were caught out because of the overload in the system and, given the absence of alternative forms of long-term funding in India, were the only providers to such critical projects.

Unfortunately, the dominant rhetoric right now is to punish the promoters and the errant bankers, and to push for recovery of collateral. This is the wrong discourse. India needs a package for infrastructure to get the economy started. Even in the US, Barack Obama provided support to the American auto industry for job protection. In India, the need to restart infrastructure projects is simply vital. It will mostly need the same promoters to be asked to start their projects and the government will need to recapitalise public sector banks or, specifically, create a package for key sectors. I imagine about Rs 50,000 crore would be needed (10 per cent of the value of the stuck infrastructure projects). As the projects start, NPAs will turn good, small and medium enterprises will start getting stalled payments from large companies, jobs will get created and the economy will pick up, making bad loans as a percentage of the total smaller. A cash-strapped government could use this crisis as an opportunity to reduce holding in public sector banks below 51 per cent and retain control by issuing a golden share or, at least, take ownership down to 26 per cent with other shareholders capped at a five per cent stake. Such a move will also help the autonomy these banks enjoy and help them address their two biggest constraints - of raising capital and in being able to pay and hire better people. But whether or not reducing government stake in public sector banks is possible, what is desperately needed is a package for starting stalled capital projects to reignite the Indian economy. We cannot wait.

The writer is chairman (Asia Pacific), Boston Consulting Group India. These views are personal

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)