The recent trade data have been cheered by the market no end, and highly optimistic current account deficit (CAD) numbers are being bandied about. While there's no doubt the CAD situation has improved, market reality does indicate that a part of such optimism may be unfounded.

An important reason for the improvement of the trade deficit data, of course, is massive contraction in gold imports. India's gold imports slumped after the government increased tax on imports three times during 2013 to 10 per cent, linked shipments to re-exports (20 per cent to be exported) and tightened financing rules to curtail a record CAD. During December, the import of gold and silver was down by nearly 69 per cent to approximately $1.77, although it was still at a five-month high.

While CAD during the second quarter of FY14 plunged to $5.2 billion or 1.2 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) from $21.8 billion (or 4.9 per cent of GDP) recorded a quarter earlier, it was as much the result of improving trade balance due to the contraction of gold import as due to surge in exports. However, the export surge can purely be attributed to the low base effect than any general improvement in competitiveness or global demand for Indian goods. Not surprisingly, export growth during November and December 2013 slowed down significantly, and not much respite is expected for the remainder of the financial year. According to the available data, exports during July-October 2012 registered an average monthly year-on-year contraction of 5.7 per cent, while during the corresponding period in 2013, it grew at a 12.3 per cent annualised rate every month.

Worryingly, however, the recent improvement in trade balance is a result of a major drop in imports, while exports barely moved. In fact, India's non-oil and non-gold and silver imports dropped by nearly nine per cent annualised rate every month during the December quarter - a clear reflection of continued economic weakness. Not surprisingly, the Index of Industrial Production numbers are sending shivers down the spine.

Interestingly, India's trade balance during the third quarter of 2013 was $29.92 billion, a tad higher than $29.76 billion recorded in the second quarter. The CAD, however, is likely to be higher during the December quarter because one can expect a slowdown in remittances since there was a major surge in flows during this period to take advantage of the attractive deposit rates that were on offer as the Reserve Bank of India was desperately trying to shore up forex inflows to stabilise the rupee as the threat of taper loomed. Going forward, import contraction will likely reduce, while export growth will peter off - both because of the base effect. Add to that a slowing economy, and the CAD for the year will likely be between three to 3.2 per cent of GDP during the current financial year.

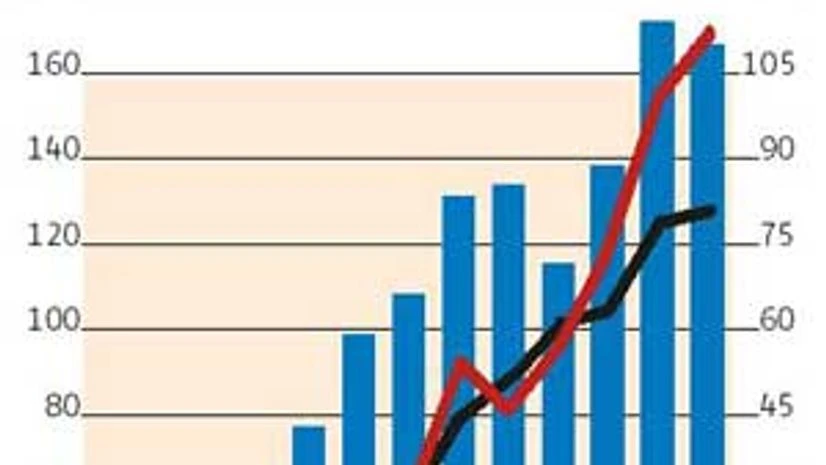

In this regard, it is interesting to note that while the recent CAD problem can be attributed to a plethora of sub-optimal policy choices of the past, high oil prices have also queered the pitch for India. According to the available data, since FY01, India's net software exports and private remittances were more than adequate in meeting India's forex needs to finance oil imports. It was during FY08 that India's oil import, for the first time, exceeded the collective inflow by more than $10 billion. Oil imports surged during the second half of the year when average oil prices went up by nearly 30 per cent, while economic growth was strong. Next year, while oil prices did surge to nearly $140 a barrel, they plunged faster as a financial crisis erupted, global growth slowed as did India's, reducing the overall oil demand, and hence resulted in positive balance.

The situation deteriorated substantially during FY12 and FY13 when average oil prices stayed persistently above $100 a barrel. The deficit shot up to $30.5 billion in FY12 and $41.2 billion during FY13. Not surprisingly, India's CAD to GDP for these two years was the highest ever recorded, 4.2 per cent and 4.8 per cent respectively.

During the current financial year, the deficit during the first six months was $17.6 billion as oil prices persisted above $100 a barrel. Clearly, oil prices above $100 a barrel remain the biggest millstone around India's neck.

To add to India's problem, the rupee might take a hit as tapering becomes progressively aggressive. While the market has priced in benign tapering, aggressive tapering has not been. Given the improvement that's visible in the US economy, our US economist expects the quantum of tapering to increase. Additionally, the US yield is inching up, which would be negative for inflows into emerging markets. In that situation, the rupee would cease to be stable (as it currently is) and will depreciate at least till the tapering is done and dusted.

The author is vice-president and India economist, Societe Generale.

These views are personal

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)