Three weeks from now, we will reach an end to speculation about what Donald Trump will do if he faces political defeat, whether he will leave power like a normal president or attempt some wild resistance. Reality will intrude, substantially if not definitively, into the argument over whether the president is a corrupt incompetent who postures as a strongman on Twitter or a threat to the Republic to whom words like “authoritarian” and even “autocrat” can be reasonably applied.

I’ve been on the first side of that argument since early in his presidency, and since we’re nearing either an ending or some poll-defying reset, let me make the case just one more time.

Across the last four years, the Trump administration has indeed displayed hallmarks of authoritarianism. It features egregious internal sycophancy and hacks in high positions, abusive presidential rhetoric and mendacity on an unusual scale. The president’s attempts to delegitimise the 2020 vote aren’t novel; they’re an extension of the way he’s talked since his birther days, paranoid and demagogic.

These are all very bad things, and good reasons to favour his defeat. But it’s also important to recognise all the elements of authoritarianism he lacks. He lacks popularity and political skill, unlike most of the global strongmen who are supposed to be his peers. He lacks power over the media: Outside of Fox’s prime time, he faces an unremittingly hostile press whose major outlets have thrived throughout his presidency. He is plainly despised by his own military leadership, and notwithstanding his courtship of Mark Zuckerberg, Silicon Valley is more likely to censor him than to support him in a constitutional crisis.

His own Supreme Court appointees have already ruled against him; his attempts to turn his voter-fraud hype into litigation have been repeatedly defeated in the courts; he has been constantly at war with his own CIA and FBI. And there is no mass movement behind him: The threat of far-right violence is certainly real, but America’s streets belong to the anti-Trump left.

So if you judge an authoritarian by institutional influence, President Trump falls absurdly short. And the same goes for judging his power grabs. Yes, he has successfully violated post-Watergate norms in the service of self-protection and his pocketbook. But pre-Watergate presidents were not autocrats, and in terms of seizing power over policy he has been less imperial than either George W Bush or Barack Obama.

There is still no Trumpian equivalent of Mr Bush’s antiterror and enhanced-interrogation innovations or Mr Obama’s immigration gambit and unconstitutional Libyan war. Mr Trump’s worst human-rights violation, the separation of migrants from their children, was withdrawn under public outcry. His biggest defiance of Congress involved some money for a still-unfinished border wall. And when the coronavirus handed him a once-in-a-century excuse to seize new powers, he retreated to a cranky libertarianism instead.

More From This Section

All this context means that one can oppose Mr Trump, even hate him, and still feel very confident that he will leave office if he is defeated, and that any attempt to cling to power illegitimately will be a theatre of the absurd.

Yes, Mr Trump could theoretically retain power if the final outcome is genuinely too close to call.

But the same would be true of any president if their re-election came down to a few hundred votes, and Trump is less equipped than a normal Republican to steer through a Florida-in-2000 controversy — and less likely, given his excesses, to have jurists like John Roberts on his side at the end.

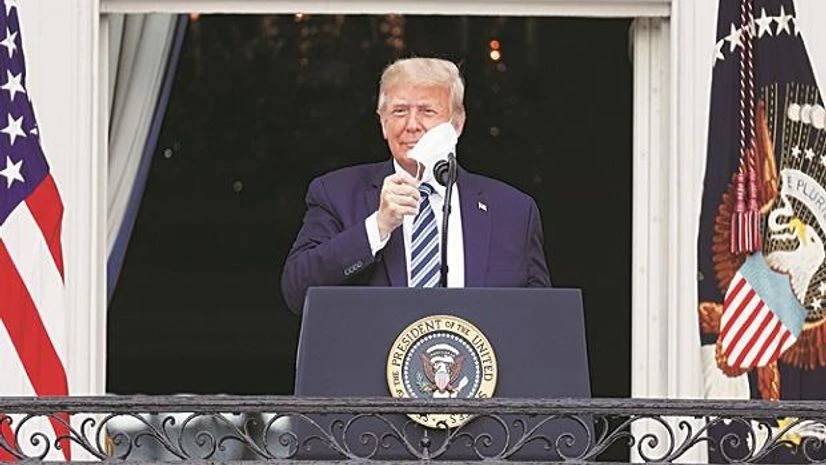

Meanwhile, the scenarios that have been spun out in reputable publications — where Mr Trump induces Republican state legislatures to overrule the clear outcome in their states or militia violence intimidates the Supreme Court into vacating a Joe Biden victory — bear no relationship to the Trump presidency we’ve actually experienced. Our weak, ranting, infected-by-Covid chief executive is not plotting a coup, because a term like “plotting” implies capabilities that he conspicuously lacks.

OK, the reader might say, but since you concede that the Orange Man is, in fact, bad, what’s the harm of a little paranoia, a little extra vigilance?

There are many answers, but I’ll just offer one: With American liberalism poised to retake presidential power, it needs clarity about its own position. Liberalism lost in 2016 out of a mix of accident and hubris, and many liberals have spent the last four years persuading themselves that their position might soon be as beleaguered as the opposition under Vladimir Putin, or German liberals late in Weimar.

But in reality liberalism under Mr Trump has become a more dominant force in our society, with a zealous progressive vanguard and a monopoly in the commanding heights of culture. Its return to power in Washington won’t be the salvation of American pluralism; it will be the unification of cultural and political power under a single banner.

Wielding that power in a way that doesn’t just seed another backlash requires both vision and restraint. And seeing its current enemy clearly, as a feckless tribune for the discontented rather than an autocratic menace, is essential to the wisdom that a Biden presidency needs.

The writer is an opinion columnist for The New York Times. ©New York Times News Service

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)