When the world's largest sovereign wealth fund decides to exit investments in coal, the ripples of the decision can be felt the world over.

Late last month, Norway's parliament decided that the $900-billion sovereign wealth fund should exit from utilities and miners that get 30 per cent of their business from coal, a move that could trigger as much as $5 billion of divestments. The companies that could be impacted by this decision - to be implemented by January 1, 2016 - include RWE (Germany), Duke Energy (the US), SSE (the UK), AGL Energy (Australia), Reliance Power (India) and China Shenhua Energy, according to a Bloomberg News report.

"Investing in coal companies poses both a climate-related and economic risk," said Svein Flaatten, a Conservative member of the parliamentary committee, which decided on the coal ban.

While this decision by the fund could inspire other large investors, the fossil fuel divestment movement has already been building up considerable steam. The most recent addition to the list of organisations eschewing coal was France's largest insurer, Axa. Chief Executive Officer Henri de Castries said he's working to sell euro 500 million of coal assets even as he triples "green investments" to euro 3 billion by 2020.

Organisations that have decided to eschew coal include the Church of England at one end and Stanford University and Oxford University at the other. Earlier this month, Georgetown University announced that it would no longer make direct investments in coal, and South Korea dropped plans to build four coal plants.

The growing corpus of "responsible investments" also adds to the challenges that coal faces. According to recently updated data from the United Nations-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), its signatory base represents $59 trillion of assets under management (AUM), against $45 trillion last year, with the number of signatories increasing to 1,380. The largest AUM increases have been seen in the last two years. "Some very big investors signed up to the Principles in the last year: Vanguard alone adds seven percentage points to our AUM. Other notable signatories over the last year include Harvard University, University of California and Bank of America's Global Wealth & Investment Management," PRI said in a statement on its website.

Contrarian view: Prominent universities that have decided not to divest include Yale and Harvard. Divestment is not the only solution. "There's a view that if they stop investing in it, or take a stance, that coal will go away. Our view is different. Coal will continue to be needed. It's going to be used by these developing nations. Our key message is if you really want to address climate change you must provide more support on an impartial basis to the reducing of emissions from coal-fired generation and other uses of coal," said Mick Buffier, chairman of the World Coal Association and also an executive at Glencore.

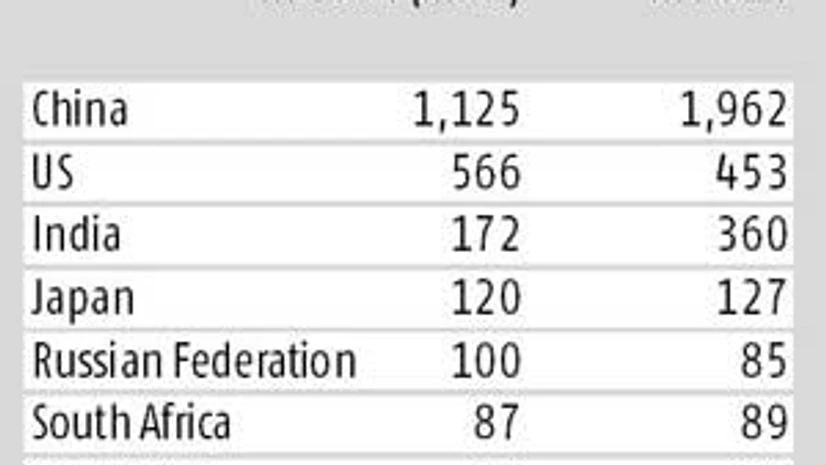

The usage of coal has been increasing in many countries, even as clean coal continues to be an oxymoron, with progress on projects that capture the carbon emissions from coal plants being tardy. Two of the three largest users of coal - China, the US and India - saw an increase in consumption in 2014 compared to the previous year, with the US being the exception, according to BP's statistical review of world energy.

Compared to a decade ago also, both China and India sharply increased consumption. In 2004, China's consumption was 1,125 million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe), which increased to 1,962 mtoe in 2014. India's consumption more than doubled to 360 mtoe from 172 mtoe in 2004. In the US, however, coal consumption of 453 mtoe in 2014 was lower than 566 mtoe a decade ago.

Global coal demand will grow at an average rate of 2.1 per year through 2019, according to the December 2014 coal market report of the International Energy Agency. This compares to the forecast of 2.3 per cent average demand growth in the 2013 report.

Coal cannot be entirely clean, but it can certainly be 'cleaner'. India's Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has proposed limiting emissions from thermal power plants - existing and new - including limits on sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and mercury emissions for the first time. The new rules also propose water consumption limits.*

Vandana Gombar is the Editor - Global Policy for Bloomberg New Energy Finance

*http://mybs.in/2RvS8s3

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)