Inside his office, rows of chairs face his desk. It’s 10.30 am and Sisodia is going through files with an officer. One of them concerns taxing car rentals services, which, Sisodia says, he will look into. Another is about retaining some “good” officers, which he insists on. The third concerns an officer who wants to go on a four-day holiday to Singapore. “Do government servants have the money to holiday in Singapore?” he asks, half in jest. “Yes, it’s cheaper than holidaying in the Andamans,” replies the officer, half serious. The leave is sanctioned.

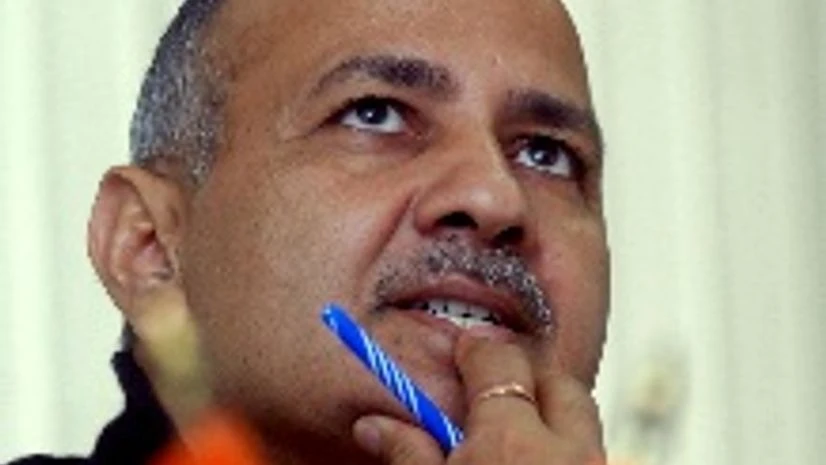

Sisodia, 43, is the man everybody seems to be seeking out. A visit to his house, a small first-floor flat across the Yamuna in Mayur Vihar, early in the morning points to his importance in the scheme of things. It’s not 9 o’clock yet and visitors are pouring in with bouquets. Sisodia has left for work, but an army of young Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) workers ensures that every visitor is served tea.

Everyone agrees that Sisodia is the man Kejriwal trusts the most, a result of years of unflinching loyalty, which reflects in his heavyweight portfolio. Their association goes back to 1998 when Kejriwal started Parivartan, an organisation that worked to empower Delhi’s poor in fighting corruption. Then a 26-year-old journalist with Zee News, Sisodia came across a small news item about it. He went back to office, dug out its press release and registered on its website. The next day, Kejriwal came to Sisodia’s house and they talked for hours together. But it took seven years before Sisodia finally decided to leave his job and get into activism, full-time.

Sisodia and Kejriwal would often station themselves outside Delhi Vidyut Board (power board) and help people write technically sound applications so that they didn’t have to pay a bribe inside and could tell the officials that they knew the rules.

According to Neeraj Thakur, a former colleague, at the news channel too, Sisodia had multiple roles: producer, anchor and shift in-charge. This ability to multitask will come in handy as he juggles multiple ministries. While at Zee News and Parivartan, he also worked as a radio jockey with Times FM. “Those were the days when Vividh Bharti ruled. Announcers would, in all formality, announce, ‘Hum Akashvani se bol rahe hain’,” says Sisodia. “We broke that mould and made it informal and chatty. Old-timers slammed it but we soon became the stars.” Something like that would later happen in politics too.

The house in Hapur’s Shahpur Fagauta village where Manish Sisodia spent his childhood

By 2003, Sisodia decided to quit journalism (he finally did in 2005) and join the team that was working to frame the Right to Information (RTI) Act. “Initially, Kejriwal was the only one I confided in,” he says. Later, when he told his friends, “they were furious and even abused me. They said I had a great job and was mad to throw it away,” he says. “I used to get Rs 57,000 as take-home salary. And I had a home loan to repay. I knew if I could raise Rs 40,000 a month, I would survive.” And though his friends were livid, they formed a pool and decided to chip in with the money he needed every month to get by. “They undertook the guarantee of my survival,” he says.

The largesse of friends prompted him to plunge full-time into working for Parivartan and RTI. “They would work in the slums of East Delhi, helping people get ration cards or power connections,” recalls Abhay Kishore, his former editor at Zee News who is now the editor of Raipur-based news channel IBC 24. “I used to sometimes meet Kejriwal at Sisodia’s house. One day Kejriwal’s wife said to me, ‘Bhai sa’ab, inhein samjhaeye na. Saara din jhuggiyon mein pade rahte hain (Please drill some sense into them. These two spend their entire day in slums)’.”

Sisodia comes from Shahpur Fagauta, a small village of Rajputs in Hapur, east of Delhi. It is a peaceful hamlet surrounded by wheat fields. The Sisodia family also has some fields here, but has sold the house where he was born. It’s an old house, with a courtyard in the front. Not far from it is the spot where his family deities reside, a small structure where the family worships its ancestors. Every Holi and Diwali, without fail Sisodia comes here to pray. “This Holi will be no different, no matter how busy he is,” says Gopal Rai, a distant uncle who lives in Pilkhuwa, a small town 10 km away.

Pilkhuwa is where Sisodia’s father, Dharampal Singh, a lecturer, moved to in 1992. He died in June last year. Sisodia sometimes visits this house, which has among its occupants, a feisty 102-year-old lady whom he considers his grandmother. It’s not a rich neighbourhood. But it’s an educated neighbourhood where a lot of teachers live. Education is Sisodia’s focus as well. He wants 20 per cent of Delhi’s budget allocated to it.

From AAP workers and colleagues to relatives, the first thing that people say when describing Sisodia is that he never loses his cool. “Between the two of them, Kejriwal might still show some emotion when confronted or in a conflict situation,” says Ajit Jha, a senior member of the party. “But Manish? Never.” Without using aggressive body language or passionate words, he is able to assert his point. Meditation, says a party worker, is what keeps him this calm. Every morning after waking up at 5, Sisodia spends some time meditating. Last year, right after AAP relinquished power in Delhi, he went to Pushkar in Rajasthan and did a meditation course to sort his thoughts out. Kejriwal also believes in the power of meditation.

AAP insiders say nobody knows Kejriwal better in the party than Sisodia. Colleagues say they share a remarkable equation, often communicating through their eyes. In times when some of Kejriwal’s closest associates turned their backs on him or questioned his “dictatorial ways”, Sisodia’s support remained unfaltering. In June last year, when senior leader Yogendra Yadav threatened to resign from the party’s political affairs committee and in a letter accused Kejriwal of promoting a personality cult, Kejriwal chose to play the matter down. It was Sisodia who picked up the cudgels for him. In an equally strong letter, he accused Yadav of fomenting factional fights within the party and gunning for Kejriwal.

Sisodia also helped Kejriwal strategise his recent landslide victory in Delhi, after the dismal show in the general elections eight months ago. “We admitted we had made a mistake, so people — both our supporters and the common man — were willing to stick with us,” he says. Detractors say Sisodia and Kejriwal dump friends when it becomes expedient: Anna Hazare, Kiran Bedi, Shazia Ilmi and several others. If the Delhi results are anything to go by, their exits have not dented AAP’s popularity. With such a mandate, Kejriwal and Sisodia have a good chance to transform Delhi.

)