HOW TO FAIL AT ALMOST EVERYTHING AND STILL WIN BIG

Author: Scott Adams

Publisher: Penguin

Pages: 257

Price: Rs 550

Also Read

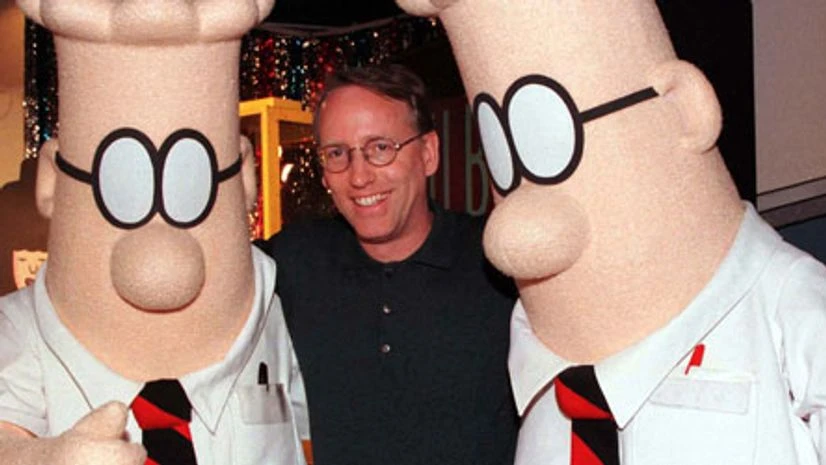

The secret to being successful is to be a serial optimist. About three decades ago, when Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert, was on the verge of being fired from his job as a teller at a San Francisco bank because he was terrible at the detail-oriented work of keeping track of people’s transactions with a pen and paper, he struck upon a novel strategy. He decided to write a letter to a senior vice-president at the bank outlining all the steps the bank needed to take to improve. As a witty aside, Adams added that he should be considered for the bank’s management trainee programme as he had been robbed twice at gunpoint while working at the bank. The senior vice-president thought his ideas “underwhelming,” but he liked Adams’ humour. A month later, Adams, 21, was a management trainee. “Somehow I had failed my way to a much better job,” he writes.

Eight years on, a manager tells Adams that the bank has decided to stop promoting white males. He brushes up his CV and applies to the telephone company Pacific Bell. By then he had nearly completed an MBA through evening classes at Berkeley and he got the job — and a big raise: “I looked great on paper. Little did they realise that looking good on paper was my best skill.”

A cartoonist probably always looks better on paper than in person, but judging from this wonderfully self-deprecating book, Adams would make a delightful dinner companion. (He even has a very useful section on not dominating the conversation at social occasions.) The book begins with his “absolute favourite spectacular failure.” Remarkably, it lives up to that billing. Still in his final year in college, Adams was called to an interview in Syracuse, New York, in the height of winter, but decided he didn’t really need a jacket because he would just be going from the car into a building. His interviewer thought his informality inappropriate and concluded the interview almost immediately.

Worse was to follow. His car “conked out” on the highway in the Catskill Mountains. The temperature was zero degrees Fahrenheit. In desperation, Adams starts running in the cold, convinced he is about to die of exposure. He promises himself that he will trade his car for a one-way ticket to California “and never see another @$#! snowflake for the rest of my life.” He is saved by a stranger and moves to California. “Thank you, failure. I no longer fear death when I go outdoors,” Adams writes.

His other failures are a mix of prosaic business problems — including trying to run a software business out of India — and seemingly life-altering challenges. One of these is when his little finger goes into spasms because he is overusing it at work and while drawing the early Dilbert comics. A specialist who happens to live down the road from him in California told him he had to change jobs as there was no known treatment. (Adams was working days at Pacific Bell, the phone company, and working on his comic strip at night.) The condition is called ‘focal dystonia’ but instead of quitting, Adams decided to put pen to paper differently or at least trick his brain into believing he was doing so: “I was literally trying to hack my brain.” He succeeds, of course. When the ailment reappears, he Googles for a software that helps cartoonists draw. His drawing time drops dramatically. (One of the unintentionally funny bits is to find that arguably the oddest looking comic strip in human history requires so much effort to draw.)

The secret to how Dilbert came to focus on business is also rooted in a serial of one setback after another. At Pacific Bell, Adams reports, 60 per cent of his budgeting job involved looking busy. His tendency to make numerical errors was cancelled out by inputs from the other departments that were “complete lies.” One begins to see the germ of the Dilbert principle at work here and this is before he is told that he can’t be promoted because of the telephone company’s need for greater diversity in its management ranks.

Adams decided to try his hand at cartoons. “It was an unlikely dream, given my complete lack of artistic talent and the rarity of success stories in that business.” Every day he writes, “I, Scott Adams, will be a famous cartoonist” 15 times and keeps at it.

A few newspapers published the comic strip, but it struggled. Happily Adams’ work at Pacific Bell had included early exposure to the World Wide Web so he put the comic strip online, hoping that people would read it and then petition their papers to run the strip. Dilbert became the first syndicated comic to run on the Internet for free. Readers’ feedback made him concentrate on the office, a rich seam because so many corporate diktats are so illogically comic. “I have poor art skills, mediocre business skills, good but not great writing talent, and an early knowledge of the internet,” he writes. “I'm like one big mediocre soup.”

Adams is joking and/or being overly modest. Just this wise commentary on politics is worth the price of the book. “When politicians tell lies, they know the press will call them out. Politicians understand that reason will never have much of a role in voting decisions. A lie that makes a voter feel good is more effective than a hundred rational arguments,” he writes. “If you're perplexed at how society can tolerate politicians who lie so blatantly, you're thinking of people as rational beings. That worldview is frustrating and limiting.” I loved this book so much I was buying copies to gift people before I was a third of my way through it.

)