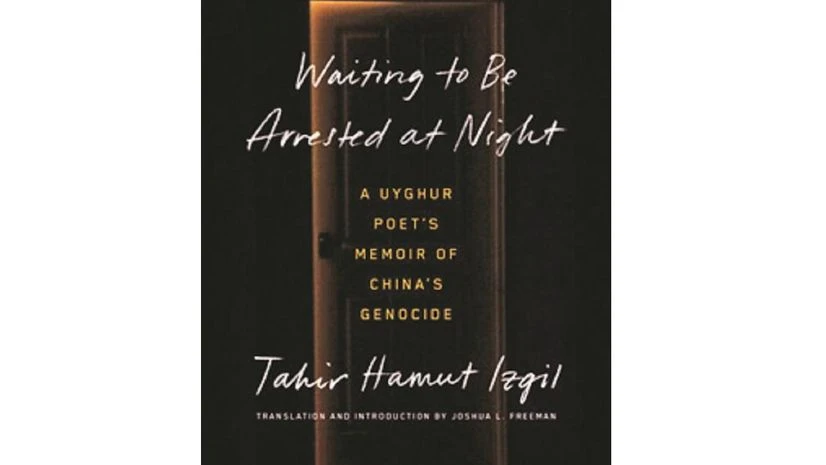

WAITING TO BE ARRESTED AT NIGHT: A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide

Author: Tahir Hamut Izgil; Translator Joshua L Freeman

Publisher: Penguin

Pages: 251

Price: $28

Also Read

The Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil’s new memoir, Waiting to Be Arrested at Night, is an outlier among books about human rights. There are no scenes of torture, no violence and few sweeping proclamations about genocide. Izgil writes with calculated restraint. As his title suggests, the terror is in the anticipation.

This is in effect a psychological thriller, although the narrative unfolds like a classic horror movie as relative normalcy dissolves into a nightmare. When the book opens, in 2009, Izgil is living in Urumqi, a city of nearly five million in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region, the traditional homeland of the country’s persecuted Muslim Uyghur minority. At 40, Izgil is happily married with two daughters, his own home and a robust circle of friends. His poetry earns him considerable renown in a culture that reveres the genre, while his work as a film director, eventually at a company he owns, pays the mortgage.

In July 2009, longstanding tension between the Uyghur and Han Chinese populations in Xinjiang turns violent, leading to riots and nearly 200 deaths, and to a government crackdown.

Izgil is not exactly a dissident, but as a prominent Uyghur intellectual, he has to avoid behaviour suggestive of ethnic nationalism in the eyes of the Chinese Communist Party. He knows the risks. In 1996, while trying to cross the border to Kyrgyzstan on his way to study in Turkey, he was arrested on spurious charges of “attempting to take illegal and confidential materials out of the country”. He is pragmatic enough to order baijiu — a potent Chinese alcohol — at a banquet to deflect suspicion that the assembled group of Uyghur poets are “devout Muslims”. But he’s also subversive enough by nature to enjoy a few laughs at the absurdities of the ruling regime.

As the crackdown intensifies in 2016, Izgil is astonished to see a neighbourhood butcher struggle to carve some mutton with a knife chained to a post — a new requirement intended to keep potential weapons out of the hands of Uyghur “terrorists.” When local shopkeepers are forced to wear red armbands, wield truncheons and whistles, and march around in formation as part of an anti-terrorist measure, he and a friend crack jokes about it. “If practically everyone is now mobilized to preserve stability, where will the violent terrorists come from?” he quips.

Before long, the humour dissipates. Checkpoints pop up, where police officers search smartphones for illegal apps, songs or photos. Books are banned, including some, issued by state publishing houses, that had been acceptable in the past. Reports filter in from other towns of mass arrests and of schools and government offices being repurposed as “study centres,” with “iron doors, window bars and barbed wire.” Uyghurs are disappearing into these centres for appearing too religious — for growing a beard or praying several times a day — or for no discernible reason. Some people feel safer in Urumqi, a cosmopolitan city, and comfort themselves with that familiar delusion: It can’t happen here.

In 2017, Izgil and his wife, Marhaba, get a call instructing them to report to the police station. They give fingerprints and blood samples, and submit to a facial scan. Through a basement corridor, they see a cell outfitted with shackles and one of China’s notorious “tiger chairs,” in which the detained can be kept in excruciating stress positions for days.

Although neither he nor his wife speaks English, and they are reluctant to leave their homeland, they resolve to emigrate to the United States. But getting out of China is so complicated that only by pretending that their elder daughter needs to be treated for epilepsy — and bribing health care workers to vouch for the diagnosis — do they eventually escape to Washington, DC.

But their departure is no triumph. When Izgil calls his mother after arriving in the United States, the police in China confiscate her cellphone and ID card, returning them only after Izgil’s father and brother sign an affidavit promising never to speak to Izgil again. His friends delete his contact info on WeChat.

Despite these precautions, some of his relatives are swept up in the mass detentions that have ensnared more than one million Uyghurs. Izgil cannot enjoy the uneasy freedom of life in the United States. With little English, he supports himself as a driver. As his translator, Joshua L. Freeman, writes in an introduction to the book, “If you took an Uber in Washington, DC, a few years ago, there was a chance your driver was one of the greatest living Uyghur poets.” Izgil struggles with writer’s block and guilt. “We live with the coward’s shame hidden in that word ‘escape’,” he writes.

Izgil is a soft-spoken poet, not an orator or activist; that’s perhaps one reason his understated account is so effective. There is credible evidence that among the abuses the Chinese have inflicted on the Uyghurs are torture, rape and forced sterilisation, but their story is not primarily one of physical harm. It’s about a government controlling its population with propaganda and technology.

Although some of the study centres have closed since 2019, mass detention persists, and China is perfecting its surveillance through other measures — smartphones, closed-circuit cameras, facial recognition and other biometric data — while extending its reach far beyond its borders, so that escapees like Izgil cannot communicate with their families. You don’t need bloodshed to instil fear.

The reviewer is an author and journalist who spent seven years in China ©2023 The New York Times News Service

)