By Advait Palepu

As shares of Gautam Adani’s conglomerate recover from an epic rout, the big question looming over the Indian tycoon is whether he can convince investors and lenders to back his capital-hungry businesses with fresh cash.

Few parts of Adani’s empire underscore the urgency of that funding for the billionaire — and also for the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi — better than Adani Transmission Ltd.

India’s largest private utility is a key player in Modi’s pledge to provide power to every Indian home. In a media blitz on Monday, it touted itself as capable of “distributing electricity to every corner of the country.”

Yet the company faces a funding gap which may force it to infuse as much as $700 million by March 2026 to fulfill existing project commitments, according to the Indian unit of Fitch Ratings — and that’s before taking into account ambitions to expand even further in coming years.

The funding needs of infrastructure builders like Adani Transmission are a major factor behind the conglomerate’s race to return to business as usual, after months of damage control and denying US short seller Hindenburg Research’s allegations of widespread corporate malfeasance. The stakes are also high for Modi, who faces national elections in early 2024 and has made infrastructure a core plank of his nation-building agenda.

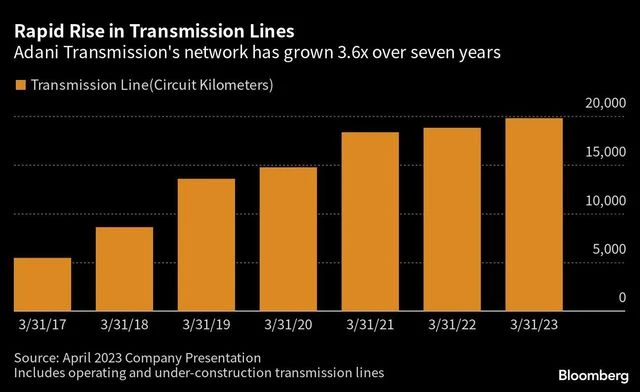

Adani Transmission, which went from being a fledgling to India’s largest private utility in seven years, has grown its asset portfolio 3.6 times to 19,779 circuit kilometers (ckm) across 33 projects.

More From This Section

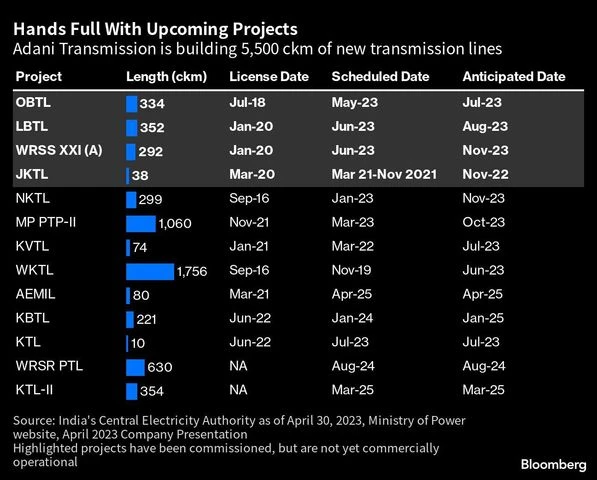

Of these, 13 projects are currently underway, but many face delays or cost overruns, including the largest one: the Warora-Kurnool Transmission line that runs through three large southern Indian states.

Others have been beset by adverse weather, pandemic-era disruptions or legal wrangles — common issues in infrastructural projects in India which makes the Adani group the rare private company that has been scaling up aggressively in this space. With India planning to add more than 27,000 ckm of transmission lines by 2025, the company’s continued expansion will be crucial for the national goal.

The utility company earlier this month announced plans to raise as much as $1 billion — one of two Adani companies looking to issue new shares for the first time since the short seller crisis which wiped more than $100 billion off the empire’s market value.

“Adani Transmission has always been aggressive on capex so the $1 billion fundraising will help them maintain growth momentum at a time when the group as a whole has had to soften their targets to come out of this logjam,” said Kranthi Bathini, director of equity strategy at WealthMills Securities Pvt.

“It might have to also raise additional debt to finance their capex requirements as the transmission business has high working capital needs,’ he said.

)

Capital infusion required by March 2026 from the company in its ongoing projects has surged as much as 60% to 57.95 billion rupees ($700 million) compared to what was envisaged before, India Ratings and Research, the local unit of Fitch Rating’s, said in a March 30 statement. This is due to cost overruns or the borrowings not being enough to support the projects, forcing the utility firm to invest more.

India Ratings revised its outlook on Adani Transmission to “negative” to reflect this uncertainty around debt funding secured for the under-construction transmission lines. Any shortfall will require the company to invest more “to meet project completion deadlines, potentially creating cashflow mismatches over FY24,” it said.

An Adani Group spokesperson said in an email that the conglomerate does “not comment on routine business matters.” “All public disclosures on business matters are disclosed when appropriate,” the spokesperson said in response to queries on how Adani Transmission plans to plug the funding gap.

‘Best Possible Assets’

Some high-profile investors are convinced about the large role units like Adani Transmission play in the country’s development.

GQG Partners’s Chief Investment Officer Rajiv Jain, one of the first investors to show support for the conglomerate after the Hindenburg attack, told Bloomberg last week that GQG had raised its investment in the Adani empire and its holdings were now worth $3.5 billion.

Jain said he is willing to buy into the group’s new share sale because “these are the best possible infrastructure assets available in India.” Praising the conglomerate for its “quality of execution,” Jain said, “Who else in India is creating such quality infrastructure assets at this scale?”

Very few private sector firms in India have the risk appetite and ability to withstand the vagaries of infrastructure development in the sprawling, unwieldy country like Adani does.

Infrastructure projects are funded by a mix of debt and capital infusion, or equity, from the company. Delays, pricier inputs or legal challenges also push up project costs.

Its largest project by length, Warora-Kurnool Transmission line, or WKTL, is facing a cost-overrun worth 6.7 billion rupees due to higher input and execution costs, India Ratings said at the end of March. The company “management confirmed that it will fully support the project to fund the entire cost-overrun,” it said in the statement.

Another project ——Adani Electricity Mumbai Infra Ltd. or AEMIL ——was slow to start as the Tata Group mounted a yearlong legal challenge against Adani’s license.

Eight Adani transmission lines are expected to be operational by March 2024 after some delay, according to data compiled by Bloomberg from company presentations and government websites.

)

Favorable Orders

The Adani Group’s effort to revert to pre-Hindenburg growth is gaining momentum from recent developments.

Besides being given reprieve earlier this month by a Supreme Court panel that found no evidence of regulatory failure or market manipulation so far in the episode, Adani Transmission has also won favorable regulatory orders to raise electricity tariffs in its operating projects to recoup past revenue shortfalls.

It’s another example of the company’s ability to navigate the difficulties of infrastructure building in India, as utilities generally cannot recoup higher costs incurred during project execution from end users as electricity tariffs are fixed through auctions. They need to petition the central or state regulator to approve higher tariffs, which usually involves a lengthy legal process.

The utility’s closely held subsidiary, Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd., got a favorable order at the end of March from the state power regulator which allowed it to raise tariffs charged to consumers by 2.2% in financial year 2024 and by 2.1% in 2025.

)

Nevertheless, many investors are still waiting to see if the unit can find the funding it needs before buying back into the stock. Its shares, which are down 67% this year, have been one of the slowest to recover from the Hindenburg rout among the group’s listed entities.

“For new buying to take place, there needs be a new investor,”said Deven Choksey, chief executive officer at local brokerage KR Choksey Shares & Securities. “We will have to wait for the proposed equity fundraise to conclude to see an appreciation of the stock.”

)