Spinners were no rarity in India. Fast bowlers too were aplenty, but after the age of Mohammad Nissar, Amar Singh, Jahangir Khan, and Devraj Puri -- which was the 1930s -- they became largely an extinct species. Only Shute Banerjee could continue till 1948.

Vinoo Mankad, Subhash Gupte, and Ghulam Ahmed were the top-performing ones among the spinners in the 1940s and 1950s. Then came Bapu Nadkarni and a few others. But all that was in dribs and drabs. Neither of them was a winning proposition. India lost much more than it won. And whenever Indian bowlers (and batsmen) did well, such as the epic performance of Mankad at Lord’s in 1952, their tour de force was talked about over decades.

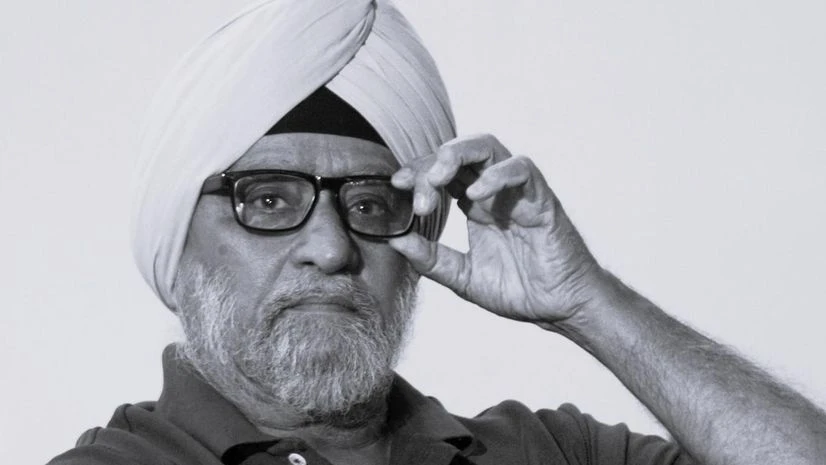

It was at this placid phase of Indian cricket, and as part of a legacy, that Bishan Singh Bedi began his career in international cricket in a Test against the West Indies in Calcutta in 1966-67. That Test is remembered not for what Bedi did. His side suffered an innings defeat. For Bedi it was almost literally initiation by fire. The crowd had set the stadium ablaze on the second day of the Test after some police action. The West Indies side had to coaxed and cajoled to play till the end.

Then on, Bedi grew from strength to strength as part of a quartet of spinners, the other three being E Prasanna, B S Chandrashekhar, and S Venkatraghavan. Bedi was the junior-most among them. He could keep a check on the scoreboard moving and get batsmen out at vital junctures of the game. The hallmark moment of his career -- and that of Indian cricket -- came in 1971, when, under Ajit Wadekar, India defeated the West Indies and England abroad. True, it was Chandrashekhar who was the architect of the victory in England, but Bedi’s contribution was never in doubt.

Success followed. Tony Lewis’s English team in 1972-73 did not have many of the best cricketers in England then. Geoff Boycott was not in the team, nor was John Snow. That did aid India’s 2-1 victory in the series. But it was widely accepted that Bedi’s superb performance would not have been diminished one bit even if England had brought its best players.

Also Read

In the afterglow of the three wins, a myth began to grow that India’s spinners were the world’s best ever. As with most myths, they were bandied about by those who knew little of the game. And they found themselves looking for a place to hide in 1974, when the Indians were mauled 0-3 in England. Sportsweek, then a widely-read magazine, said in its headline: “Spin won’t serve for ever.”

Another moment of disgrace that summer came when the Indian team, just after losing the second Test, arrived 40 minutes late at the high commissioner’s tea party. The high commissioner was hopping mad and gave the team a stern rebuke. The mercurial Bedi said, perhaps not to the high commissioner straight in his face, that all this upbraiding was only because the team had lost.

Bedi proved spin was not lost “for ever”. India under Pataudi did well at home against the West Indies the following winter. And then Bedi took over as captain from him in 1975-76 – an unusual thing to happen in those days for a bowler to be made captain. But he was successful. Under him in the West Indies, India scored more than 400 in the fourth innings of the Test and won. Till then in the history of cricket it was only the second time that such a thing had happened.

In Australia, which were a depleted side because of the Kerry Packer phenomenon, India again did well but lost. And doing well owed much to Bedi. The defeat in Pakistan in 1978 signalled his playing-days were nearing their end. And he lost his captaincy because of the bad decision to bring himself on to bowl at a crucial juncture when quick bowlers were required to operate. Imran Khan demolished him in an over and ensured Pakistan’s victory.

There were several sides to the personality. There was the jovial and magnanimous side which showed up when he greeted Vivian Richards, saying, “Welcome, Sir Vivian, to your own country.” Richards complimented him, saying how fearful he was of the Indian spinners.

He could be acerbic as a commentator. The word “batter”, some say, was started by him in the 1980s. Bedi could have corrected them by pointing out that the word was used in Tom Brown’s School-days (published in 1857).

The most intriguing was his relationship with Sunil Gavaskar. After Bedi named his son Gavas Inder Singh (probably the “Inder” part owes itself to Inder Singh, the footballer), there was a bitter falling out. Things came to such a pretty pass that Bedi once said: “Sunil, I am ashamed I ever played cricket with you.” They mended fences later.

One relationship sustained Bedi all his life. He started international cricket under Pataudi. And when Bedi was asked for comments after the Tiger died, he said: “Contact me later. I can’t speak now.”

The man deserves to be placed in the category of greats such as Syd Barnes, Clarrie Grimmett, Bill O’Reilly, and Shane Warne.

)