Early trends suggest that, in the period post Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), China has demonstrated superior gains when compared to other participating nations. Studies suggest that India's decision to abstain from RCEP stemmed primarily from a commitment to shield its manufacturing sector. A comprehensive understanding of this situation necessitates an exploration of the challenges faced by Indian manufacturing, not only from China but also from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) through the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) route.

Comparing FTAs

India and China entered FTAs with ASEAN around the same time, in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Despite the synchrony in timing, the trajectories of the two FTAs have diverged.

Before the FTAs were established, both India and China had a slightly negative balance of trade (BoT) with ASEAN countries. Notably, China had already established itself as the "factory of the world" for nearly two decades, while India had experienced substantial growth during the go-go years of 2003-08. Post-FTA, China's BOT with ASEAN surged into a surplus, reaching $159 billion in 2022. In contrast, India experienced a notable shift in its BOT with ASEAN, plunging into a $45 billion deficit in 2022 as depicted in Figure 1.

)

)

The surge in imports from ASEAN to India, tripling to $89 billion, was accompanied by a doubling of exports to ASEAN, reaching $44 billion from a more modest baseline.

Bilateral trade

More From This Section

Examining total bilateral trade, the disparities are even more pronounced. The China-ASEAN FTA led to a 460 per cent increase in trade between the two partners, soaring from $212 billion in 2009 to $975 billion in 2022. Meanwhile, India's trade with ASEAN grew by 295 per cent, albeit on a base four times lower than China-ASEAN, rising from $45 billion in 2008 to $133 billion in 2022. Moreover, with an average domestic inflation rate of 4 per cent, the value of India’s exports to ASEAN in 2008, which was 19 billion, would be equivalent to $31 billion in 2022.

This reflects a modest 40 per cent increase in exports over 13 years. According to advocates of FTAs, bilateral trade typically surges in the post-liberalisation period. In the context of India-ASEAN, the increase has been relatively modest.

Furthermore, the stickiness in India's composition of imports from ASEAN over the years, both before and after the FTA, is particularly striking. Despite the FTA's aim to foster diversification, the reliance on two vital raw materials, palm oil and coal, has endured. These materials, intrinsic to India's imports from ASEAN, are significant contributors, as illustrated in Figure 2A.

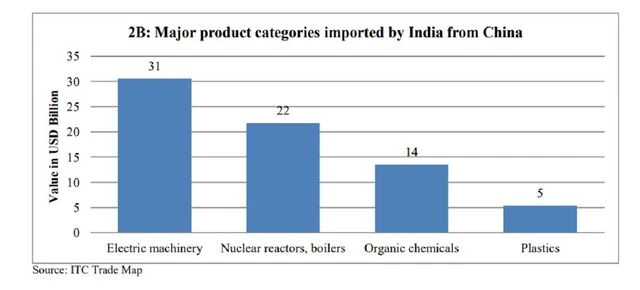

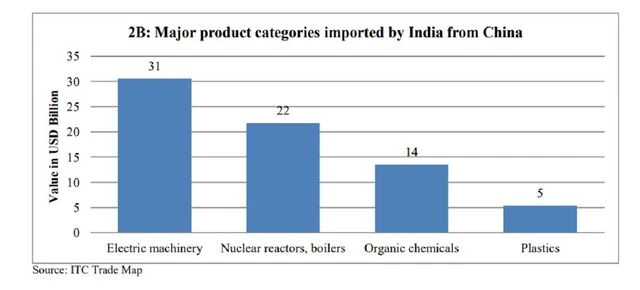

Noteworthy is the fact that beyond these raw materials, specific product categories, such as electric machinery and equipment, nuclear reactors and boilers, organic chemicals, and plastics, collectively constitute 45 per cent of India's imports from ASEAN in 2022, a proportion that has remained consistent since 2008. Intriguingly, these same product categories also account for a substantial 72 per cent of India's imports from China in 2022 (Figure 2B). This parallel composition raises questions about the expected transformative impact of the FTA and emphasises the enduring patterns in India's trade dynamics with both ASEAN and China. One may argue that the FTA with ASEAN was intended to diversify and decrease reliance on China. However, the data suggests otherwise. India's import basket from both ASEAN and China is predominantly influenced by common chapters.

)

)

)

)

Changing FDI trends

The trends in FDI shows a staggering picture. Post-FTA, Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into ASEAN has been staggering, exceeding $100 billion from 2009 to 2022 (see figure 2). The percentage of Chinese FDI in ASEAN's total FDI stock rose from 5% in 2009 to over 14 per cent in 2022.

)

)

)

)

Notably, FDI figures in 3A do not include the inward FDI data for Vietnam, Myanmar and Singapore. The FDI data for Vietnam and Myanmar was not available in the IMF FDI database.

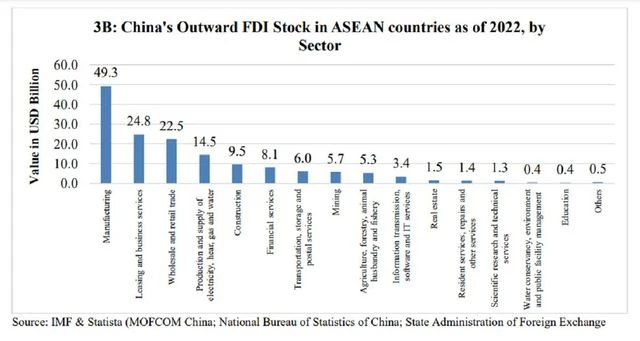

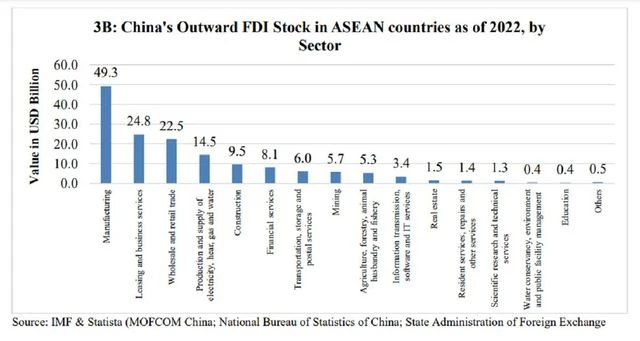

Despite the availability of data for Singapore in the IMF, we have chosen to exclude Singapore's FDI data since it is not considered a major manufacturing base within ASEAN. Interestingly, Chinese FDI outflow data from 2018 reveals substantial investments in Vietnam, receiving USD 10 Billion worth of FDI from China between 2018 and 2022. Moreover, 50 percent of FDI from China to ASEAN countries has gone to the manufacturing sector (see figure 3B). As RCEP comes into effect, the lines distinguishing these two countries are expected to blur even further, signaling potential challenges and shifts in the dynamics of the region.

Reassessing benefits of India-ASEAN FTA

The advantages of India's FTA with ASEAN appear unclear. While the BoT seems to get larger every year, India’s inward FDI, except from Singapore which is not primarily a result of the FTA, also does not seem promising. With limited benefits, this FTA prompts queries about the rationale behind granting access to Indian markets for such marginal gains.

One major concern of the ongoing FTA with ASEAN is the issue of excessive dependency on China. Currently, India heavily relies on China for its imports, ranking among top 5 import sources for 6700 out of 10,764 product categories (at HS8). Moreover, with considerable Chinese interest in ASEAN in terms of investments, particularly in manufacturing and an overlapping FTA, engaging in an FTA with ASEAN can be likened to an indirect FTA with China. China's ability to influence markets- manipulate prices, control exchange rates, and exert leverage can significantly impact the trade dynamics of RCEP members, including ASEAN, with far-reaching consequences. Thus, as ASEAN integrates more closely with China following RCEP, there is a need for stringent rules of origin.

Theories posit that trade can be a positive sum game. However, one critical assumption is that countries are similar in terms of their ability to influence the markets. However, with China this does not hold. Therefore, it is imperative for India to prioritize creating a level playing field to safeguard the interests of its domestic industry.

Gupta is a consultant at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry and Hussain is senior research fellow at the Centre for WTO Studies.

These are the personal opinions of the writers. They do not necessarily reflect the views of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

)